The Twilight Zone, Season One (1959-60)

These are capsule reviews that were originally published at @astimelessasinfinity

Episode 1: Where Is Everybody?

An amnesiac (Earl Holliman) wanders through an abandoned town, trying to figure out where everyone is and how he came to be there. Food is still cooking, cigars are still smoking, but nobody is around. Jocular at first, he slowly loses his mind.

Not the strongest episode, although it introduces a lot of themes that the show would continue to address, especially isolation. (Could the show’s low budget have something to do with this? Fewer actors, fewer paychecks.) Holliman never shuts up, which could have been about worry over whether you could keep an audience’s attention with one character who never talks, but I got to where I was wishing he’d shut the hell up.

Serling assembled a hell of a crew: director Robert Stevens was a veteran of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and Oscar-winning cinematographer Joseph LaShelle was a master of shadows and dread.

Episode 2: One for the Angels. Aired October 9, 1959

A pitchman (something of a vanished job–think Family Dollar in a cart) named Bookman, played by the always excellent Ed Wynn, is informed by Death (Murray Hamilton, looking and sounding suspiciously like Rod Serling) that he’s gonna die at midnight. Bookman manages to outsmart Death, so Death chooses a replacement. Horrified, Bookman tries one last pitch to try to change Death’s mind.

I adore this episode, partly because I think Ed Wynn’s huckster pitchman is the best character I’ve encountered during this viewing marathon. (You’ve seen/heard him before: he was the Mad Hatter in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland and Uncle Ed in Mary Poppins). I love that Death so closely resembles Rod Serling, a nice acknowledgement of the weird and kind of cruel relationship his narration has with the events of each episode. Director Robert Parrish was a former child actor who became a hell of an editor (Oscars for Body and Soul and All the King’s Men) whose directing career wasn’t as interesting.

Episode 3: Mr. Denton on Doomsday. Aired October 16, 1959

Denton, the town drunk (played by Dan Duryea), is a former gunfighter who’s trying to drink away bad memories. He’s tormented by local toughs including one played by a very young Martin Landau. After an encounter with a salesman named Fate, his aim miraculously improves and he regains his neighbors’ respect. But he knows that when word gets out, fame-hungry gunslingers are going to try to prove themselves against him.

I like seeing faces I remember from 1940s and 1950s films pop up in these episodes. Dan Duryea played sleazy, slippery, antagonistic bad guys in a bunch of films I love, including “Scarlet Street,” “Criss Cross,” and “Winchester 73.” Seeing him here as a shameless drunk, and then as a man resigned to his fate, gave me even more respect for what Rod Serling was doing with this show. And again we have a character (Henry Fate) standing in for Serling, commenting on Serling’s role as the master of ceremonies. Good stuff.

Episode 4: The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine. Aired October 23, 1959

Former Hollywood superstar Barbara Jean Trenton (Ida Lupino) spends all day in her mansion watching 16mm films of her glory days. Her agent Danny Weiss (an excellent Martin Balsam) gets her an audition with a studio head (Ted de Corsia), but she’s outraged when it turns out she’s supposed to play a small role as a mother. Danny arranges for her former costar Jerry (Jerome Cowan) to stop by, but she rejects the older man in Coke-bottle glasses she sees before her, preferring the dashing leading man she shared the screen with. “If I wish hard enough, I can wish it all away,” she tells Danny. She’s right.

This is my second favorite episode in the first season (after “Time Enough at Last,” obviously). It features a female lead! Who’s played by one of my favorite actresses! Who, although she’s obsessed with her looks and living in the past, is still a fully formed character. We can wonder (without really needing to wonder) why our culture is so enamored of portrayals that mock women who try to hold on to their youth, when it also demands that they stay young-looking but doesn’t demand the same of men; however, I like that this episode also presents us with a former leading man who got old, lost his hair, and manages a chain of grocery stores.

Fun fact about the Instagrammer: I have three 16mm projectors and regularly show 16mm films at public screenings through the nonprofit that I run, so I’m especially fond of seeing Barbara’s projector in action throughout this episode.

Episode 5: Walking Distance. Aired October 30, 1959

A sad advertising executive (future Oscar winner and future murderer Gig Young) stops for car repairs near the town where he grew up, and he decides to hoof it to see what his hometown looks like now. He gradually realizes that he’s somehow walked into his own past, encountering his own parents and younger self, which leads to near-tragic results.

This is acclaimed as one of the best TZ episode ever, and I… don’t agree. I disliked it; it’s one of my least favorites so far. It feels like something Ray Bradbury would toss off during his lunch break, and it sinks into the sentimental mawkishness that some of Bradbury’s work was prone to. It was probably intended as homage, too (there’s even a character named Mr. Bradbury), since Rod Serling approached Bradbury to write for the series. He did end up writing episodes, although only one script (“I Sing the Body Electric” during season 3) was produced during the original run. Anyway, I gather that I’m in the minority on this one. Convince me that I’m wrong!

Interesting fates of Twilight Zone actors: Gig Young killed his wife and himself in 1978.

Episode 6: Escape Clause. Aired November 6, 1959

A misanthropic hypochondriac (David Wayne) strikes a deal with the devil (Thomas Gomez, the first Hispanic person to be nominated for an Oscar) for eternal life in exchange for his immortal soul. Because he’s a petty jerk, he uses his immortality to commit insurance fraud in a series of accidents instead of, you know, traveling or reading sci-fi. When he grows bored of that, he finds himself in a situation where the fine print on his contract with the devil might be useful.

This one is weird: it’s… funny? A little? It’s jaunty about its dickhead protagonist, and there’s real comedy in the petty schemes he concocts, because I think if most of us had eternal life, we’d be thinking about something more than insurance fraud. It’s not always funny: the death of his wife, treated for laughs, reminds us how little use this show had for women most of the time. But the effect is a kind of dark comedy that had me rooting, just a little, for Wayne.

The series that had already put some of my favorite washed-up actors to work (Dan Duryea, Ida Lupino) used a director whose work I admire: Mitchell Leisen, a versatile 1930s-1940s director who was adept at musicals (The Big Broadcast series), comedies (especially Hands Across the Table and Midnight), melodrama (Hold Back the Dawn makes me cry), and others. By 1959, he was done in Hollywood and was doing TV.

Episode 7: The Lonely

Convicted murderer (Jack Warden) is imprisoned on an asteroid (Death Valley is a good substitute), visited every few months by a spaceship crew bringing supplies. The spaceship captain brings him a gift: a lifelike female robot (Jean Marsh, later Queen Bavmorda in Willow) to keep him company. She learns to be human from him, and he falls in love with her. But what happens when he’s offered a chance to return home without her?

This one is fucking bleak, shades of Tom Godwin’s immortal story “The Cold Equations.” And everyone in this episode pronounces “robot” as “RO-butt.” Weird. Aside from the female centered episode 4, there aren’t many womenfolk in the series yet; finally we get an important female character and she’s a RO-butt. Baby steps. Director Jack Smight went on to direct an adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man.

Episode 8: Time Enough at Last.

One of the immortals, one of the best sci-fi things ever committed to celluloid, it’s based on a short story by Lynn Venable. John Brahm is behind the camera, and if you haven’t seen his divine noirish 1940s psychodramas Hangover Square and The Lodger, you need to remedy that stat.

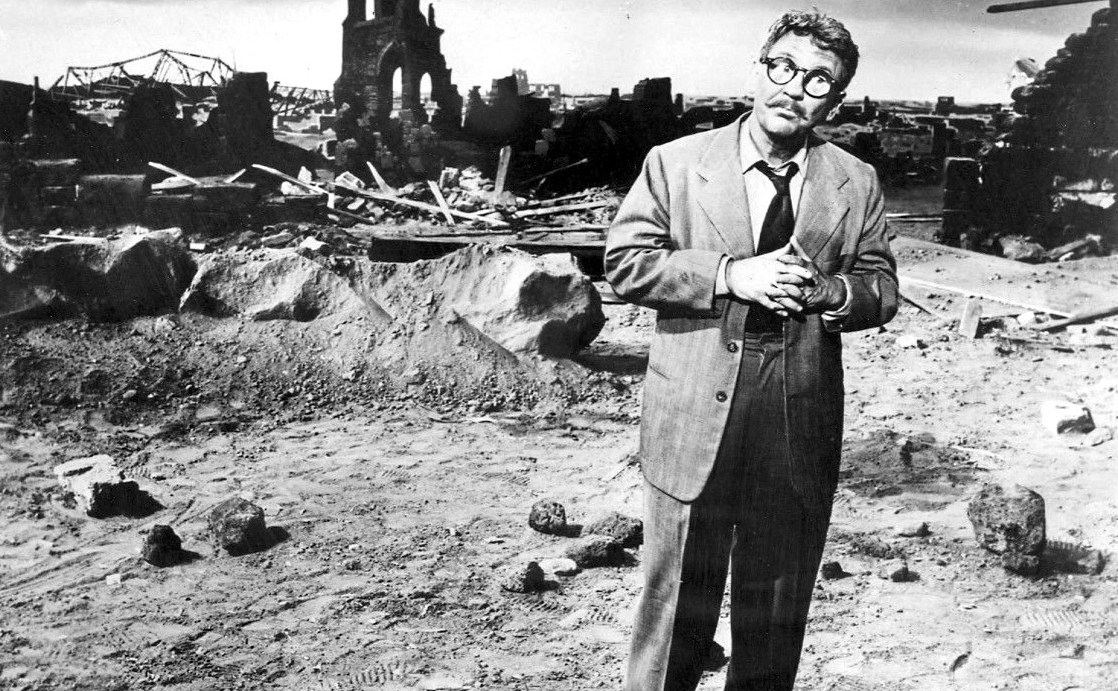

A hapless bank clerk (Burgess Meredith unrecognizable in Coke-bottle glasses and salt-and-pepper hair) doesn’t want to wait on customers, or listen to his boss, or play cards with his wife’s friends. He wants to read. But his boss threatens to fire him if he catches him reading again, his hectoring wife (source material by a woman did not equal forward-thinking about gender roles) defaces his books, and a nuclear holocaust destroys everything and everyone but him. Then he finds the ruins of the library.

This one is bleak, too, but not in a depressing manner; it’s more like a cosmic joke kind of thing, and I was giggling throughout because although I remembered the ending I didn’t remember how we were going to get there. And it’s so understated; Meredith underplays it, quietly protesting the unfairness instead of raging at the world. And it contains the greatest TBR scene in the history of the world.

Episode 9: Perchance to Dream. Aired November 27, 1959

A guy with a heart condition and an overactive imagination (Richard Conte) yells “doc ya gotta help me” and also “you can’t help me doc” at a psychiatrist (John Larch). He can’t go to sleep because nightmares will kill him, but he can’t stay awake anymore because that will kill him too. You see, in a recurring series of dreams, a carnival vixen named Maya (Suzanne Lloyd) tries to scare him to death. When he realizes that the good doctor can’t help him, he tries to leave, but was it all a dream!?!?

So, this one doesn’t make much sense, and that’s fine! It’s the first episode not written by Rod Serling, and I’m not linking those two facts because some of Serling’s don’t make sense. Sense is overrated. It was written by Charles Beaumont, who published an excellent essay about being approached by Serling to work on this series before it was produced; his description of reading immortal scripts like “Time Enough at Last” before anyone else gave me chills. Chills!

I love Richard Conte in this. He often played emotionally complex tough guys in 1940s and 1950s: his face looks like it’s chiseled from stone, but also like he could start crying at any moment. But the real catch here is director Robert Florey, who brought everything he learned as a B-movie director of expressionist masterpieces like 1931’s Murders in the Rue Morgue” and 1937’s Daughter of Shanghai. The carnival scenes are truly nightmarish, which is great because they’re supposed to represent nightmares.

Episode 10: Judgment Night. Aired December 4, 1959.

Carl Lanser (Nehemiah Persoff) finds himself disoriented on the deck of a cargo liner crossing the Atlantic in 1942, with no memory of how he got there. The ship has lost its convoy and is in danger of being destroyed by the German submarines that patrol the area. As the night progresses, he becomes convinced that something terrible is about to happen, and it might just be his fault.

Serling was a paratrooper during World War II and was wounded several times; his daughter later said he suffered from what is now known as PTSD. Throw in his obsession with karma (although that’s not really the right word: more like “we all got it comin’ to us,” because it’s almost always a good time to quote Clint Eastwood movies), and you get a situation that I was going to discuss as a soldier who, in the course of doing his job, racks up sins that he must atone for. But it’s not atonement, unless eternal punishment counts. “We can ride the ghost of that ship every night for eternity.”

John Brahm directs again. Have you watched The Lodger or Hangover Square yet? Dear god, go do it. I’ll wait here. They’re both online, the former on Youtube and the latter on Dailymotion. The fog and the deserted corridors of the ship, the terror of any light that might give away the ship’s position, the hushed voices, the anxiety over every creak. It’s brilliant.

Episode 11: And When the Sky Was Opened. Aired December 11, 1959.

An astronaut (Rod Taylor) was one of the two pilots of an experimental aircraft that mysteriously disappeared and then reappeared on its inaugural flight beyond the atmosphere. While visiting his fellow pilot (Jim Hutton) in the hospital, he reveals that there were in fact three pilots, that the third has been erased from existence, and he’s afraid he’s being erased as well.

An adaptation of Richard Matheson’s story “Disappearing Act,” this one manages to not make a hell of a lot of sense while building an unbearable atmosphere of dread, the kind of foreknowledge that your world is going to end, and you know how it’s going to happen, but nobody will believe you, and it wouldn’t matter if they did. You’re fucked. And it features Gloria Pall, who once got kicked off of TV for being too sexy, as well as Jim Hutton, the father of Oscar winner Timothy Hutton, who I once sat next to on the train in Manhattan. He smelled nice, like smoked turkey, and I was too shy to tell him he’s amazing.

I was thinking about implementing a ratings system, like a five-star scale, for these episodes, but I’m not sure how much use a ratings system would be if everything got 4.5 or 5 stars. This one gets 5.

Episode 12: What You Need. Aired December 25, 1959.

A petty crook named Renard (Steve Cochran, and this show was sometimes a little obvious with character names) discovers that meek peddler Pedott (Ernest Truex) has the magical ability to sell people exactly what they need, even if they don’t know they need it: some cleaning solution, a bus ticket, a pair of scissors. The fox decides he’s found a golden goose, but it might not be what he needs.

Based on a story by Lewis Padgett, aka C.L. Moore and Henry Kuttner, surely the greatest female-spouse-and-male-spouse writing team in history. It had already been filmed as part of Tales of Tomorrow, a weekly sci-fi show from 1952 that I had never heard of before this. It’s on the Internet Archive.

Rod Serling was 36 when this show went into production; Renard is at least the fifth 36-year-old male protagonist in the first 12 episodes. Hmm. John Brahm directs again. GO FORTH AND WATCH The Lodger DAMN IT. I was positive that Arlene Martel, who plays Girl in Bar, was the first Asian-American actor with a speaking role in this show, but it turns out she was an Armenian who often played Asian characters. And I think I’d love this episode if not for the show’s tendency to over-explain things. I really didn’t need Pedott’s soliloquy about why he gave Renard the last gift, and it ruined the ending a bit. I suppose they felt they had to ensure that every single person in the audience would understand what was going on.

Episode 13: The Four of Us Are Dying. Aired January 1, 1960.

Small-time grifter Arch Hammer (Harry Townes) has the ability to change his face to look like anyone he wants to (and he’s 36, obviously). But he’s a small-time grifter, so he uses his magical ability to do small-time things: impersonate a dead musician, steal money from a gangster, and escape being killed by the gangster’s cronies. But eventually his choice of faces leads to tragedy.

Hey, it’s the first episode that I think is bad. (I didn’t like “Walking Distance” but I understand the appeal; this one is just dead space.) I wish Serling wouldn’t have given the game away in his opening narration. It recovers a bit from that with the first impersonation, of a recently deceased jazz trumpeter (Ross Martin). The scene between Martin and his grieving girlfriend (Beverly Garland) is heartbreaking because Garland is so completely destroyed by his death, and she rebuilds herself in front of us when she thinks he’s alive. But the rest doesn’t live up to that scene.

John Brahm directs again. I understand that you still haven’t watched The Lodger or Hangover Square, and I want you to know that you’re making a huge mess of your life. Based on a story by Logan’s Run cowriter George Clayton Johnson, with a score by a young Jerry Goldsmith.

Episode 14: Third from the Sun. Aired January 8, 1960.

It’s closing time at a weapons of mass destruction factory, and Will Sturka (Fritz Weaver) is afraid that there’s going to be a nuclear war within the next couple days. He and his coworker Jerry (Joe Maross) plan to steal an experimental spaceship that will carry them and their families to a recently identified planet where human-like people live. But snooping coworker Carling (Edward Andrews) is trying to stop them.

OK kids, in the olden days before Netflix, when TV episodes aired, viewers didn’t know their titles, and probably didn’t know they even had titles. So they didn’t know that this episode depended on a twist that’s given away in the title. Aside from that annoyance, this is a first-rate episode. The setting is perfect, a plausible near future where people might rightly believe they’re being spied on in their homes, and where the threat of exposure by snooping coworkers was real. There’s a card game that begins with the adults trying to pretend nothing is wrong and ends with an unbearable visit by Carling that had me sweating.

Richard Bare directs; he wrote one of the best books about film directing, The Film Director, and also directed almost every episode of Green Acres, so you know he’s good. It’s based on a story by Richard Matheson, and Harry Wild, cinematographer of Murder, My Sweet and Nocturne, is behind the camera. Everything is top-notch.

Episode 15: I Shot an Arrow into the Air. Aired January 15, 1960.

The first manned mission outside earth’s atmosphere goes terribly awry as the ship crashes onto an uncharted asteroid, killing most of the crew. The three survivors, including Donlin (Edward Binns) and Corey (Dewey Martin), face the prospect that they’ll never be found, and they’re running out of water. Extreme situations lead to extreme behavior.

Rod Serling heard a pitch by a friend at a dinner party, asked for a treatment, paid Madelon Champion $500 for her idea, and here we are. Big steps. The episode is solid, with the two main characters providing a philosophical faceoff between Randian selfishness and the ideals of community. It’s not terribly hard to figure out the twist, but it doesn’t detract from enjoying the episode.

Stuart Rosenberg directs: he of The Amityville Horror and Cool Hand Luke and The Pope of Greenwich Village got his start on TV. He later taught Darren Aronofsky and Todd Field at the American Film Institute. I’m constantly amazed by and thankful for the level of talent Serling was able to attract to this series.

Episode 16: The Hitch-Hiker. Aired January 22, 1960.

Kids, it wasn’t so long ago that there weren’t interstates, and if you wanted to drive from New York to California, you did it on a mix of local roads, turnpikes, and two-lane highways. Nan (Inger Stevens), driving to a new life in Los Angeles, learns some of the perils of that drive: we meet her when she’s just survived a blowout, she later almost gets hit by a train, and she has to endure a road closure by just sitting there and waiting. And there’s the creepy hitchhiker she sees in every town, down every side road, silently beckoning with his thumb, no matter how fast or far she drives.

The episode is based on a radio play by Lucille Fletcher, spouse of composer Bernard Hermann and also the author of the fantastic noir Sorry, Wrong Number. In the original play, the main character was a man, so let’s all thank Rod Serling for changing it to a woman. And unlike male main characters, she’s not 36.

This is often listed among the best of the series, and it was very good, but the incessant voiceover narration bugged me like it always does. Interesting facts: Inger Stevens died of an overdose at 35, and the voice on the phone at the end is that of Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella’s wicked stepmother.

Episode 17: The Fever. Aired January 29, 1960.

Flora Gibbs (Vivi Janiss) wins a weekend in Las Vegas, but her hectoring husband Franklin (Everett Sloane) disapproves of gambling. When a drunk insists that Franklin play a one-armed bandit, Franklin wins, and now he has the fever.

I love that the slot machines look like they were manufactured by the same companies that made film projectors and power tools, all bolts and gears and burnished steel. I love that Franklin carefully puts his tie on while lecturing his wife about morality before he goes back down to the casino. I love that it’s Everett Sloane, one of Orson Welles’s regulars (Arthur Bannister in The Lady from Shanghai). But I don’t love this episode, which is by turns screechy-preachy and silly. There’s a moment where it could have been great, when Franklin is lying in bed, sweating, thinking about the machine, wondering if he really heard it say his name. But it goes somewhere else.

Episode 18: The Last Flight. Aired February 5, 1960.

“Such a thing doesn’t happen every day.” “Well, it happened today.” A WWI biplane pilot takes off in 1917 and lands at a US Air Force base in France in 1959. If that weren’t weird enough, it turns out that he’s a coward who had abandoned his fellow pilot, and he has one chance to make up for it.

I have a soft spot for this episode, as I have a soft spot for WWI aviation, and for John Monk Saunders, Fay Wray’s doomed husband, who wrote several films and/or stories made into films about WWI aviators, including Wings, Ace of Aces, and my personal favorite The Eagle and the Hawk. And The Last Flight, which has nothing to do with this episode, but which is a sad and lonely film about PTSD among pilots before they had a term for it.

Anyway, this was great. Solid performances, and a nice demonstration of the idea that if you shout your irrational thing loud enough, the audience doesn’t have a chance to notice how silly it is. It’s also Richard Matheson’s first episode as screenwriter, which is something to celebrate. And it’s the first time the show used the line from Hamlet about “there are more things in heaven and earth…” but probably not the last. I’m impressed that Serling held it back this long.

Episode 19: The Purple Testament. Aired February 12, 1960.

Toward the end of World War 2 in the Pacific, a lieutenant (William Reynolds) is tormented by the newfound ability to foresee which of his fellow soldiers are going to be killed. Darrin Stevens from Bewitched–I mean Dick York, his fellow officer, tries to get him to have his head examined, but that will have to wait until after the next battle, if there is an after.

As he’s done a few times in this first season, Serling exorcises a few of his personal WW2 demons (he was wounded a bunch of times and his daughter said he had PTSD). “Picture a man, tormented by his past, who uses a popular TV show to work through his issues…” Another solid episode.

Richard Bare, who lived to age 101, had five wives, and directed almost the entire run of Green Acres, is behind the camera. In addition to Darrin Stevens from Bewitched, this episode also features Sam Peckinpah regular Warren Oates and film director Paul Mazursky. And we end with Shakespeare quotes in two straight episodes! Now we’re cooking.

Episode 20: Elegy. Aired February 19, 1960.

A trio of astronauts from 2185 who think they’re lost in space 650 million miles from Earth set down on an asteroid that looks like Earth of the 20th century, if Earth of the 20th century was populated by living mannequins. Finally, one of the mannequins talks to them. He has bad news.

How bleak is this episode? I’ll let you decide after hearing two lines of dialogue, one of which could be the motto for the entire series. “While there are men, there can be no peace,” and “Fate, a laughing fate, a practical jokester with a smile that stretched across the stars, saw to it that they got their wish.” Behind the scenes: it’s written by Charles Beaumont, and one of these days I’ll OCR the essay he wrote about when Serling first approached him about writing for the series. It contains props made for Forbidden Planet, sound effects reused in Star Trek. There is a continuum. There’s a clip at the end in which Serling defends his ability to write scripts for women by pitching next week’s episode starring Vera Miles. I like that people expected more of him, and that he tried to work on it.

Episode 21: Mirror Image. Aired February 26, 1960.

Millicent (Vera Miles) is waiting for a bus that’s a half-hour late. When she complains to the management, they respond that she needs to chillax and stop pestering, because this is the third time she’s asked. But she doesn’t remember asking before. Could there be a doppelgänger from a parallel universe trying to replace her in this world?

Unlike a lot of the actors I recognize from these episodes, who were more or less washed up, Vera Miles was an A-list star when she did this episode, with John Ford’s The Searchers and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man in the rearview, Hitchcock’s Psycho filming around the same time as this episode, and Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance up next. And she’s good, dear readers. She’s very good. She spends most of the episode being befuddled and increasingly spacey, but there’s a quick shot of the doppelgänger (whoops, I spoiled it) that’s just a masterpiece of wordless acting. With a smirk and a… I don’t know what it was, but she looks like an imperfect double full of nefarious intent.

Quick takes: How to treat people you think are mentally ill: (1) call the cops, (2) watch as they drag her away screaming. Netflix asks if I want to skip the intro, but I never do. I also always watch the credits. I like the sinister-looking packages wrapped in paper behind the baggage check counter. John Brahm directs again. I know most of you still haven’t watched The Lodger and Hangover Square, and the one person I do know watched the latter didn’t like it but he’s wrong. Heed my advice! If you like classic suspense movies with a dash of melodrama, go watch them.

Episode 22: The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street. Aired March 4, 1960.

After something (an asteroid? an alien ship?) flies over Maple Street, the power goes out. A kid who’s been watching too many Twilight Zone episodes suggests that it’s probably an alien invasion and that there are probably people among them who are actually space monsters in disguise. Things go downhill quickly from there.

This is one of the greats. It’s a distillation of Serling’s struggle between hopelessness and hope for humanity, coming down, as he usually does, on the side of hopelessness. When humans are unsure of a situation, “they pick the most dangerous enemy they can find, and it’s themselves.” The episode might be about the Red Scare, or about the pushback against the nascent Civil Rights Movement, but to Serling, it’s just about us. The only improvement I could imagine is ending the episode before we discover what caused the power to go out. More props from Forbidden Planet are on display. Yay! The cast is full of “hey, it’s that guy!” kinds of actors, including Claude Akins, who I spent half the episode convinced was an Andy Griffith stunt double.

Episode 23: A World of Difference. Aired March 11, 1960.

Arthur Curtis, a 36-year-old businessman of some sort, freezes when trying to call his office. Someone yells “cut!” and suddenly Curtis finds himself on a film set, surrounded by people who think he’s Gerry Raigan, a famous actor down on his luck and trying to make a comeback with a film about Arthur Curtis, a 36-year-old businessman of some sort. He’s a bit confused.

I loved this episode, and I’m here to tell you why. It’s nice to have a purpose.

Eileen Ryan, playing Raigan’s angry ex-wife OH MY GOD SHE’S SEAN PENN’S MOM plays her hatred of him with an intensity of feeling that’s surprising, given the vintage of the episode SHE’S CHRIS PENN’S MOM TOO. It must have been pretty shocking in a TV show for a former spouse to express such vehement hate for her ex. And she’s playing his secretary in the movie-within-the-episode, in which she’s friendly and eager, and thus obviously she’s an actress of great range and when this episode aired she was pregnant with two-time Oscar winner Sean Penn while his older brother Michael was probably with a babysitter. Maybe she’s just looking for someone to dance with. Please comment if you get that reference.

Another Bewitched connection! David White, who played Darrin Stephens’s boss, plays Curtis/Raigan’s agent. Ted Post, director of the Dirty Harry film Magnum Force and the pilot of Cagney & Lacey, is behind the camera. Richard Matheson, famous sci-fi writer, is behind the typewriter, and maybe that explains the weird sort of… hope? Is it hope? In a Twilight Zone episode? I mean, sure, it’s kind of a crazy deluded hope, but it’s hope.

Episode 24: Long Live Walter Jameson. Aired March 18, 1960.

Walter Jameson (Kevin McCarthy, most famous as the dude from the first Invasion of the Body Snatchers), a history professor known for his moving lectures about the Civil War, wants to marry the daughter (Dody Heath) of his boss (Edgar Stehli), but there’s a catch: his boss has discovered that Jameson is hundreds of years old, definitely too old for his daughter.

Another great one! I’m sure I’m going to be disappointed with later seasons, but this one has to be one of the best seasons of any TV show ever. Don’t argue with me because you’re wrong. This is an interesting take on the whole “oh man I just discovered that you’re secretly an immortal being” story. At first it’s about the boss’s fear of death, as he tries to learn some secret of eternal life from Jameson; then it shifts to being an elegy for the people an immortal leaves behind. Jameson wants to go through with the marriage even though he’s lived through at least a handful of previous marriages, and Stehli doesn’t want that to happen to his daughter. It’s moving and humane, the cruel hand of fate nowhere in evidence. Charles Beaumont wrote it.

Estelle Winwood, who appears as one of Jameson’s former wives, kept acting until she was 100 years old, making all of the episode’s hand-wringing about 70-year-old Prof. Kitteridge’s advanced age seem a little silly (although the average life expectancy for someone born in the 1890s would have been less than 50 years). Oddly enough, all of the stars of this episode lived to ripe old ages: Kevin McCarthy died at 96, Edgar Stehli died at 89, and Dody Heath, who quit acting in 1974, is still alive and kicking at 90. This has been today’s dose of Twilight Zone trivia. Thank you for stopping by.

Episode 25: People Are Alike All Over. Aired March 25, 1960.

Two astronauts, the hopeful Marcusson (Paul Comi) and the terrified Conrad (Roddy McDowall), take off in a spaceship bound for Mars. They should have listened to Conrad.

I like keeping the synopses as short as possible, but in fact, the spaceship crashes, Marcusson dies, and Conrad meets human-looking mind-readers who go to great lengths to make him feel comfortable, including building him a split-level ranch house to live in… just for a little while.

Whoa nelly, Serling’s surliness is on blast. “You’re looking at a species of flimsy little two-legged animal with extremely small heads, whose name is Man.” The punch line is there in the episode title, although viewers back in 1960 wouldn’t have known it: people are alike all over, which McDowall (all gawky and sexy in his gawky, sexy Roddy McDowall way) says ruefully once he learns his fate.

Fun facts! Mitchell Leisen is behind the camera again. Four actors from this episode later appeared on Star Trek, including Susan Oliver in a similar role. The episode is based on a story by sci-fi writer and editor Paul Fairman, but significantly rewritten to save on budget and to increase the level of irony to Serlingesque heights. End of fun facts.

Episode 26: Execution. Aired April 1, 1960.

A murderer named Joe Caswell who is about to be hanged by the neck until dead in 1880 is suddenly transported to 1960 New York by the Professor from Gilligan’s Island, who quickly learns that he’s made a terrible mistake that has nothing to do with a three-hour tour. Caswell experiences what a difference 80 years makes and then finds something that Serling calls justice in his closing monologue, but I call a poor ending to an otherwise great episode.

This one had so much promise. There’s so much it does right: the incredibly moving monologue that Caswell delivers to the Professor (but not Mary Ann because she’s not in this episode) about killing to survive, Caswell’s horrified reaction to the cacophony of 1960 New York City, his reaction to seeing a western TV show. I think Serling was even commenting a little on the necessary cheapness of his own western set by showing its mirror on a pub television. But the ending is a lame sort of deus ex machina that goes for the neat irony that Serling loved so much instead of something greater about modern society.

Fun facts! It was based on a story by George Clayton Johnson, the cowriter of Logan’s Run and the writer of the first Star Trek episode “The Man Trap”; and there was only one fun fact today.

Episode 27: The Big Tall Wish. Aired April 8, 1960.

An aging boxer named Bolie Jackson (Ivan Dixon) breaks his hand right before a comeback fight and is pummeled unconscious… or is he? His neighbor, a boy named Henry Temple, wishes an extra special big tall wish that Bolie would win, and for a moment it seems like it might work, if only Bolie believes in it.

This is a really uncharacteristic episode for a number of reasons. First, it’s groundbreaking in that it features an almost all-African American cast, which TV audiences in 1960 wouldn’t have been used to. Kudos to Rod Serling for breaking some barriers! It also features the most minimalist boxing match in history, one that uses positively avant garde techniques including freeze frames, silence, and below-the-mat shots. And it features that weird thing, hope: in a series that’s characterized by people having their hopes crushed by the faceless forces of the universe or the awfulness of humanity, we’re urged to believe in the power of a kid’s wish.

Ivan Dixon is probably best known from Hogan’s Heroes, which means today he’s probably not known at all. But he was a force, active in the civil rights movement, and the director of a truly revolutionary film, The Spook Who Sat by the Door, which was so controversial that the FBI had it suppressed. Go watch it, or better yet, watch it and also read the source novel by Sam Greenlee.

Episode 28: A Nice Place to Visit. Aired April 15, 1960.

Rocky Valentine (Larry Blyden), a small-time crook, is shot by the police after he robs a pawn shop. He’s awakened by the jovial Mr. Pip (Sebastian Cabot), who informs Rocky that he can have anything he wants: a nice apartment, $700, whatever he wants to eat. Because bullets don’t affect Pip, Rocky realizes he’s dead, and this must be heaven. But as Bono once said, “I gave you everything you ever wanted, it wasn’t what you wanted.” That’s right, I went there.

Wow, Mickey Rooney was the first choice to play Rocky, and that would have been aces, although Blyden’s not bad. Charles Beaumont, who wrote this episode, wanted Rod Serling to play the role, and that would have been great as well. Cabot reminded me of Thomas Gomez’s superior performance as Satan in “Escape Clause,” and overall this episode reminds me of that one’s jaunty, winking tone. There was one terrifying moment, though: Rocky fires a gun at Mr. Pip, and although it’s loaded with blanks, we can see sparks and other debris flying at Cabot’s face. I immediately thought of Brandon Lee dying after being shot by a blank on the set of The Crow, and it reminded me of how much I hate the Stone Temple Pilots song “Big Empty,” although I generally like them. And I guess my mind wandered a bit.

Episode 29: Nightmare as a Child. Aired April 29, 1960.

Helen (Janice Rule, wearing such ostentatious fake eyelashes that it distracted me throughout) comes home from work to find a fair-haired moppet named Markie (Terry Burnham) sitting outside her door. The girl seems to know an awful lot about Helen, including the reason she should be afraid of the handsome stranger (Shepperd Strudwick) who is about to knock on the door.

Seriously, it seemed like Janice Rule was having a hard time opening her eyes under the weight of those lashes. And she has such expressive eyes (go google her) that I don’t know why you’d do that to her. But anyway, this episode suffers from what I hereby dub The Rod Serling Tendency To Explain Everything to Death(TM). The ominous stranger takes several minutes to explain what he’s been up to the past several years; the detective and the doctor at the end stop to psychoanalyze Helen and offer interpretations of what the little girl means. And the closer, where Rule encounters another little girl, is just too much. Come on, Rod! Can’t you be more of a sourpuss?

Episode 30: A Stop at Willoughby. Aired May 6, 1960.

James Daly plays Gart Williams (not to be confused with illustrator Garth Williams), a veritable Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (look it up) who works in a high-pressure ad agency for a jowly horrific boss with the Dickensian name of Misrell (Howard Smith) and has an upwardly mobile wife (Patricia Donohue) who shouts things like “My tragic error was to get married to a man whose big dream in life is to be Huckleberry Finn!” He falls asleep on the train home and wakes up in the 1880s; a conductor informs him that they’re at Willoughby, which looks like an outtake from the James Cagney film The Strawberry Blonde (look it up, then watch it), and Gart is welcome to get off the train and stick around. One of these days, maybe he will.

Hoo boy! I was well on my way to hating this episode, which I thought was heading toward a treacly sub-Bradbury hokum, so imagine my surprise (and the surprise of everyone within two blocks) when the twist occurred and I bellowed with laughter. That ending, especially in light of how deceptively obvious everything that came before seemed, puts this one on the top shelf, if I had shelf where I kept my favorite Twilight Zone episodes, although I don’t because I watch these on Netflix. And I’m not the only one: this was remade as a Mark Harmon TV movie and referred to in the TV show Thirtysomething.

Oscar-winning editor Robert Parrish is behind the camera, and I’m going to credit him for the great montages of yelling admen and juggling telephones.

Episode 31: The Chaser. Aired May 13, 1960.

An obsessed young man named Roger (George Grizzard) is obsessed with a young woman named Leila (Patricia Berry) who does not love him, so obviously he seeks out a possibly satanic alchemist named Daemon (John McIntire) and buys a love potion from him despite Daemon’s warnings (“Frankly, you’d get the same shake from a cocker spaniel”). Lo and behold, Grizzard finds it really annoying to be loved like a cocker spaniel, so obviously the only solution is poison. OR IS IT!?!?!

I don’t like this episode, although there are a few things I like quite a bit about it. Daemon’s delightful book-lined study, which seems to consist only of towering bookshelves. It’s based on a story by British fantasy writer John Collier that’s been adapted in several other settings. Um. That’s it.

Episode 32: A Passage for Trumpet. Aired May 20, 1960.

Joey Crown (Jack Klugman), an alcoholic trumpet player, decides to pawn his trumpet and jump in front of a truck when it appears that he’s completely washed up. He wakes up in some sort of limbo where nobody can see or hear him, except a mysterious trumpet player named Gabe (John Anderson).

This is a strange, gentle, uncharacteristic episode anchored by three perfect scenes featuring Klugman, one of the great character actors in screen history. His opening monologue about how he can no longer play without being drunk is a heartbreaker, but even the mid-episode religious hokum with “Gabe” (which I choose to interpret as Joey’s internal monologue about whether life is worth living) is lovely, helped along by a bravura show by cinematographer George Clemens. And then the closing rooftop scene, where Joey’s life expands a little bit when he meets a new neighbor (Mary Webster), made me tear up a little. It’s enough to make me forgive the wall-to-wall white-boy lounge-jazz. Serling actually says “life can be rich and rewarding and full of beauty.” What is this, the Twilight Zone or something?

Episode 33: Mr. Bevis. Aired June 3, 1960.

An eccentric named Bevis (Orson Bean) lives a life of disarray, and today he falls down the stairs, gets into a car accident, and gets fired. His guardian angel J. Hardy Hempstead (Henry Jones) materializes and offers to fix everything… for a price.

OK, enough with the cute and heartwarming. I don’t mind it once in a while, and sometimes it works out really well (like the last episode I posted about), but I also expect a hearty dose of existential dread and maybe some alien planets once in a while, so I’m hoping this season ends with a bang. I need it after this one, in which the message is basically “be yourself.” There are three episodes left.

Episode 34: The After Hours. Aired June 10, 1960.

Marsha (Anne Francis), in search of the perfect gift, ends up on the ninth floor of a department store that has only eight floors.

That’s more like it! Mannequins that move, and a classic “am I crazy or is everyone just trying to make me think I’m crazy” storyline. And I’m ecstatic that I could construct a one-sentence synopsis that manages to convey the creepiness of the premise. I give this one an A+, because I keep forgetting what scale I’m using, or even whether I’m using a scale.

Episode 35: The Mighty Casey. Aired June 17, 1960.

The last-place Hoboken Zephyrs have their season saved by the arrival of Casey, a goofy guy who pitches like a machine.

I don’t usually like the comic episodes as much as the more serious ones, but this one is a lot of fun. It helps that the cast is so uniformly excellent. Former boxer and paratrooper Jack Warden, whose comic timing is impeccable, returns to the show (he was the marooned prisoner in episode 7, “The Lonely”) as the hard-luck manager. He was a late addition to the cast—Paul Douglas originally played McGarry, but he died of a heart attack on the day after the episode wrapped, and he looked so sick and exhausted in the footage that Serling decided to reshoot on his own dime.

Brilliant editor Robert Parrish directed the reshoots; he must have the best batting average of any TZ director, because all three of the ones he helmed (this, “One for the Angels,” and “A Stop at Willoughby”) are home runs. I just ran out of baseball references.

Weird facts about Twilight Zone actors: gawky southpaw Robert Sorrells, who plays the robot Casey, died in prison after being convicted of murdering a guy who threw him out of a bar. This was his first role.

Episode 36: A World of His Own. Aired July 1, 1960.

Gregory West (Keenan Wynn), a milquetoast playwright, is interrupted in his romancing of shy schoolteacher type Mary (Mary LaRoche) by the arrival of his shrewish wife Victoria (Phyllis Kirk). He defends himself with an outlandish story: he created Mary by describing her in his dictaphone, and he erased her by clipping out the tape and burning it in the fire. Victoria thinks he’s a loon and threatens to have him locked up, but he can prove it.

So, the tone in Richard Matheson’s script is comedy, but it’s a mean-spirited, misogynist comedy about a Mediocre White Man creating sexy playthings for himself without regard for their feelings. It was probably pretty funny at the time; hell, at another time I might have found it funny. But it’s somewhat redeemed by one of the funniest moments in the first season, Serling’s only screen appearance as part of the episode, when West interrupts his omniscient narration about fantasy by tossing an envelope containing Serling’s tape into the fire.

And that’s the end of season 1.