Shock Theater from the Cinema Dementia Collection

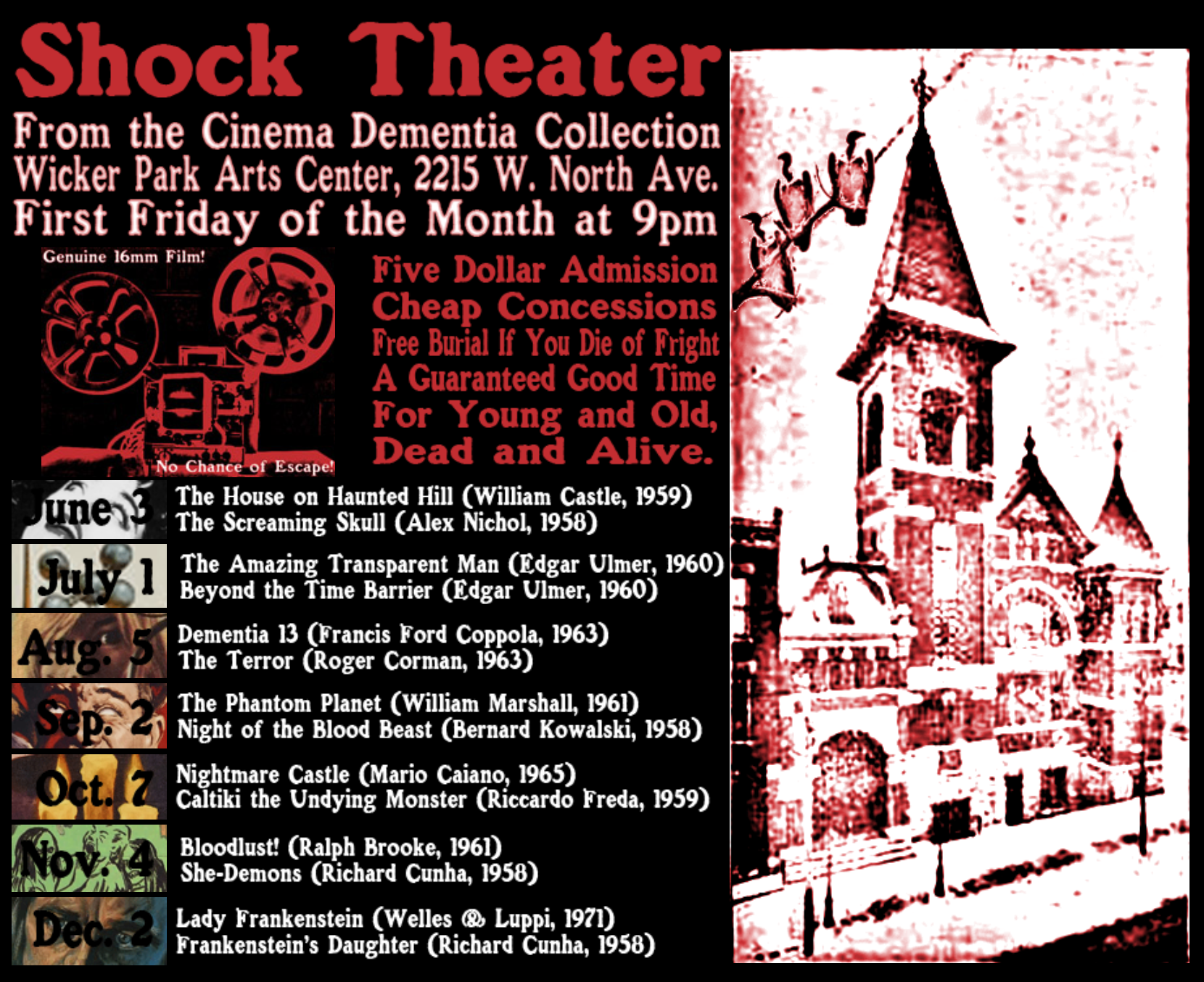

In 2011, my friend Chip Hess and I launched a short-lived underground film series called Shock Theater from the Cinema Dementia Collection. We showed monthly double features of low-budget horror and science fiction films from 16mm prints in the basement of a Wicker Park (Chicago) arts center that used to be a church. We built a “projection booth” out of plywood that elevated our two Elmo 16mm projectors above the audience’s heads. I even built a switching box for seamless audio transitions. We offered “five dollar admission, cheap concessions, free burial if you die of fright, and a guaranteed good time for young and old, dead or alive.”

Shock Theater comes from a long history of B-movie programming, starting with Universal Studios’ packaging of several of its classic horror films for TV audiences in 1957. These programs usually had a creepy host introducing the films; the most famous host was Zacherley in Philadelphia. Here in Chicago, viewers could tune in to WKBD-TV on Saturday nights for Shock Theatre, which Terry Bennett hosted as Marvin, a sort of demented beatnik. Cinema Dementia is Chip’s name for his extensive collection of 16mm film prints. He came up with a bunch of possible double features, and we pared the selections down to the seven craziest and most interesting programs.

The programs were:

June: William Castle’s The House on Haunted Hill and Alex Nicol’s The Screaming Skull

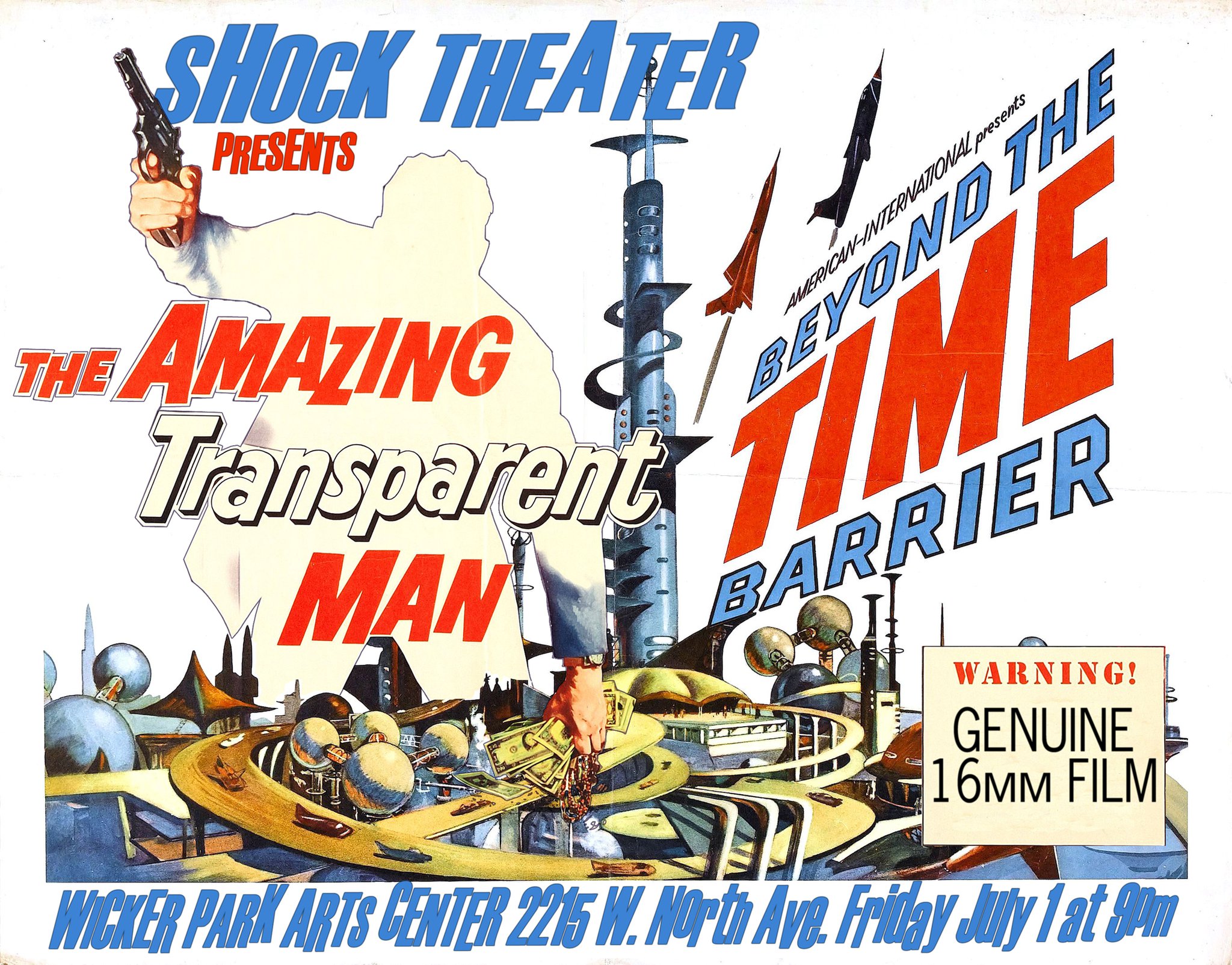

July: Edgar Ulmer double feature, The Amazing Transparent Man and Beyond the Time Barrier

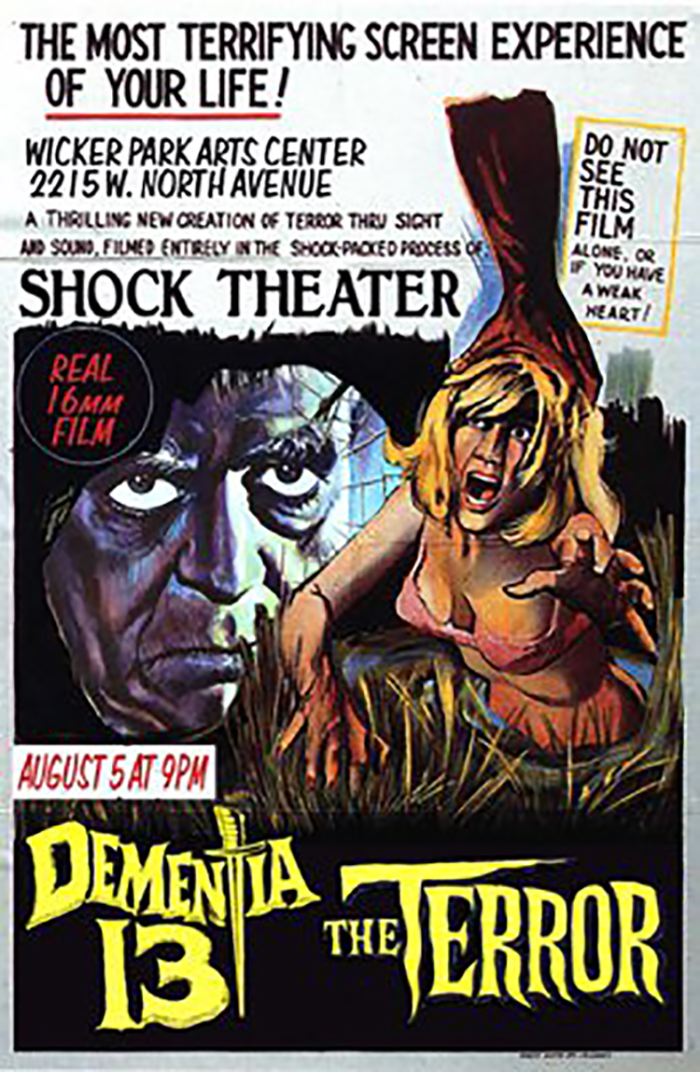

August: Francis Ford Coppola’s Dementia 13 and Roger Corman’s The Terror

September: William Marshall’s The Phantom Planet and Bernard Kowalski’s Night of the Blood Beast

October: Mario Canino’s Nightmare Castle and Riccardo Freda’s Caltiki the Undying Monster

November: Ralph Brooke’s Bloodlust! and Richard Cunha’s She-Demons

December: Welles & Luppi’s Lady Frankenstein and Richard Cunha’s Frankenstein’s Daughter

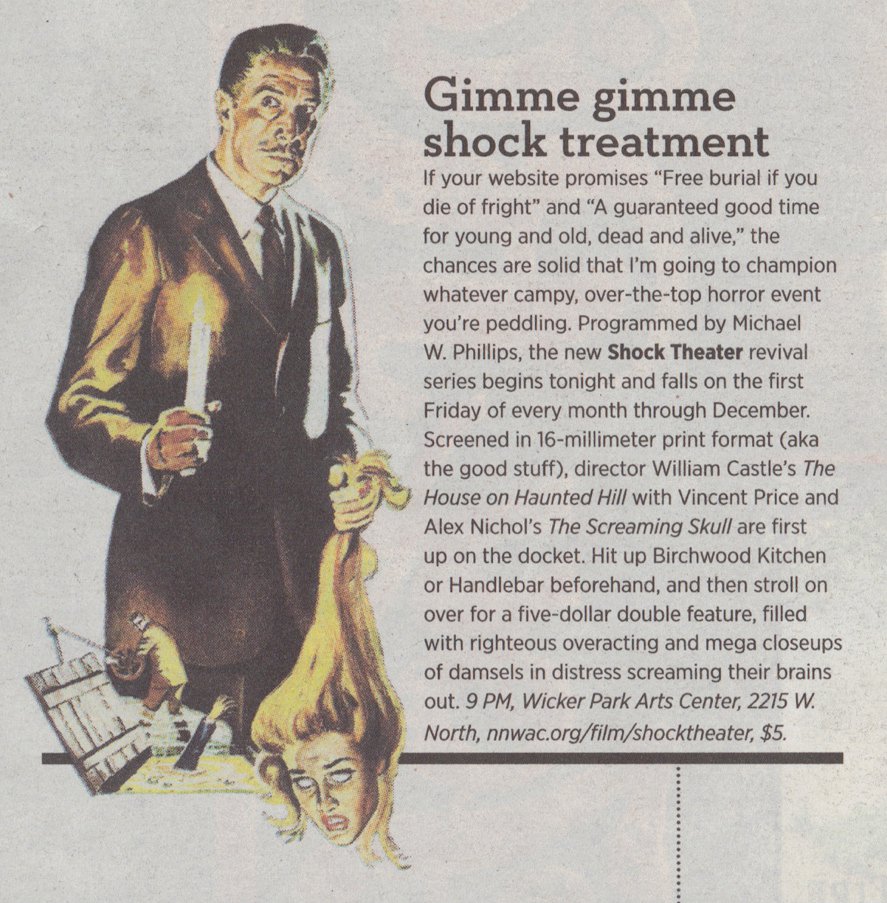

People were excited about it. We got coverage from the Chicago Reader and the now-defunct Red Eye newspaper. Our first screening was a huge success: we drew more than 75 people into a space that comfortably seated 40. It was a double feature of William Castle’s The House on Haunted Hill and Alex Nicol’s The Screaming Skull. Theatrical viewers of Haunted Hill had been treated to “Emergo,” a theatrical gimmick that included a plastic skeleton floating above the audience on a pulley system. We wanted to put on a good show, so I bought a blow-up skeleton from a Halloween store and attempted to rig up a pulley system. When it failed during the screening, I ran through the audience waving it above my head.

It wasn’t perfect. There was no AC in the basement, and the summer nights were sweltering. The art center kept screwing up its scheduling, so we often had to wait for a poetry group to finish their readings before we could start setting up. The crowds got gradually smaller. Finally, we decided to shut it down. I didn’t make a penny from it. It was the most fun I’ve ever had as a film programmer.

Below, you can see the posters I created for each double feature, the website I made, the trailer that Chip made, a couple of radio interviews with us, and an interview with me.

Shock Theater Trailer by Chip Hess

Radio Interview, Those Were the Days, WDCB Radio

Radio Interview, WGN Radio

Susan Doll, Shock Theater: “We Guarantee to Bury You Without Charge if You Die of Fright”

Movie Morlocks blog, May 30, 2011

Chicago has turned into a real movie-lover’s dream town. From mainstream theaters to art houses to midnight movie series to revival programs, cinephilia is spreading across the city. This Friday, June 3, marks the beginning of a new film program called Shock Theater, organized by Michael Phillips, former programmer of the Bank of American Cinema. On the first Friday of every month, Phillips will screen a double feature of classic-era horror films in Chicago’s hip Wicker Park neighborhood.

Nothing could be better than seeing films on a big screen with an appreciative audience, especially for the low price of $5.00, except for perhaps seeing them projected on celluloid. Each film will be projected from a 16mm print. The series opens with The House on Haunted Hill and Screaming Skull, followed by The Amazing Transparent Man and Beyond the Time Barrier on July 1. August brings two films from Roger Corman’s studio, Dementia 13 and The Terror, while September offers The Phantom Planet and Night of the Blood Beast. In October, Phillips will show two Italian horror flicks, Nightmare Castle and Caltiki the Undying Monster, while November brings Bloodlust and She-Demons. Finally, Shock Cinema celebrates the Christmas season with Lady Frankenstein and Frankenstein’s Daughter on December 2. Michael Phillips graciously agreed to be interviewed about Shock Theater, the joys of programming, and the movie-going scene in Chicago.

Q: What is Shock Theater and what is the Cinema Dementia Collection?

MP: Shock Theater from the Cinema Dementia Collection is a new monthly horror film series in Chicago. At 9pm on the first Friday of every month between June and December (and hopefully beyond), we’ll be showing a horror or sci-fi double feature at the Wicker Park Arts Center (the former St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Wicker Park, 2215 W. North Ave.) on genuine 16mm film. Those films come from the Cinema Dementia Collection, which is the name local film collector Chip Hess gave to his extensive collection of B-movies.

Q: What is your background in film, and how did you get into film programming? What are your past programming ventures?

MP: I don’t have any scholarly background in film, although I once took a class called The Modern Horror Film, so maybe that qualifies me for this venture. I started out as a fan who lived in a small town with one video store. Once my friends and I had watched everything that was relatively new, we moved on to the black and white stuff. Eventually I realized I had seen a good chunk of the films nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, so I decided to see them all (I finished that task in 2009). Amidst the prestige films were the genre pictures that sometimes snagged a nomination, so I got into film noir, classic horror, screwball comedy, you name it.

In 2004 a friend who ran the projectors at the then-LaSalle Bank Theater was leaving for grad school and asked if I wanted to take over. I projected there for the next six years, adding programming to my resume around 2006; by the end, I was the sole programmer. Bank of America, who took over LaSalle Bank, closed the Cinema in December 2010, but thankfully my former colleagues Julian Antos and Becca Hall have continued the tradition with their Northwest Chicago Film Society.

In addition to that, I program the Chicago International Movies & Music Festival, and last year I started doing neighborhood screenings that turned into my new nonprofit screening series, South Side Projections.

Q: Chicago offers several specialty or alternative venues that offer audiences a chance to see classic-era movies, such as the Silent Film Society of Chicago, the Northwest Chicago Film Society, and Facets’ Night School. What accounts for the popularity of seeing old films on the big screen? Or, why are these programs/venues able to survive?

MP: Well, they’re not all able to survive, especially when their evil banker owners sell the buildings they’re housed in. [The Bank of America exhibited no interest in the cinema series that bore its name, though it was a 35-year community institution. The bank arrogantly closed the Cinema amidst local protests.] But yes, Chicago is a pretty great place to see classic films, and there are a lot of options. I feel like part of it is sort of circular: There are a lot of great places to see films, which creates an audience hungry for more of this stuff, which helps other, new ventures succeed. Facets’ Night School is a good example of that—you know that there are people who (1) love films, and (2) have demonstrated that they’ll go great distances to see them (like the far northwest side, or the south side with Doc Films, etc.). You look around and realize that nobody’s doing a certain thing—like presenting “schlocky” films in a setting that emphasizes there’s something of value in them, and you do a fun little presentation that helps people identify that value. Presto, you have an enthusiastic crowd willing to come out for those midnight screenings in the dead of winter in Chicago. It might seem crazy, but not if you look at the elements that went into the decision. This might just be me rationalizing the decision to do Shock Theater, but I feel like it has a good chance of succeeding.

Q: The films for Shock Theater will be projected from 16mm films. What are the advantages of projected films? Where do you get your prints?

MP: Film just looks better. Yeah, it might be scratched up or spliced, but even a beat-up 16mm film print is going to look better than most projected DVDs (and these prints are excellent!). You can argue about why that is, or say that it’s just a matter of preference—scratches and splices vs. washed-out picture and/or that weird blocky pixelation you get with DVD projection. But we film lovers know the difference. This is how they were meant to be seen! (You know, late at night, with a crowd of people, in a church basement.) That’s really the key, though: Even if you’re watching a projected DVD, the real draw is seeing movies with a crowd. Comedies are funnier, romances are weepier, and horror films are scarier when you’re experiencing them with a few dozen or a few hundred other people. That feeling of being part of something, of being in a big group of people sharing an experience: You can’t have that on your Netflix streaming (or, dear lord, your iPhone). The prints, as I mentioned above, come from Chip Hess’s Cinema Dementia Collection.

Q: What is the significance of the name Shock Theater?

MP: Shock Theater was initially Universal Studios’ packaging of their classic 1930s and 1940s horror films for television in the late 1950s. They’d encourage local TV stations to hire a host to present the films for late-night audiences. They were really popular, so Universal followed them with Son of Shock. It’s pretty much become a catch-all phrase for presenting low-budget films, usually on television, but here we’re using it for semi-theatrical presentation of horror and sci-fi B-movies from the 1950s and 1960s.

Q: Each week, Shock Theater presents a double feature. Can you explain the pairings?

MP: Each double feature has a theme. June is haunted houses, July is films directed by Poverty Row genius Edgar Ulmer, August is Roger Corman productions, September is terror in outer space, October is Italian horror films, November is “Castaway Dismay” (films about bad things happening to people stranded on islands), and December is the lovely ladies of Frankenstein.

Q: Which films are you particularly excited about?

MP: Can I tell you a secret? When I programmed this, I hadn’t seen any of the films. Not a single one. That’s the great thing about programming: You’re in charge, and you get to show films you want to see. And to be even more honest, I’m hardly “programming” this series, as Chip gave me a list of possible double features and I picked these seven from it. So I’m really excited about all of them, and the low-key environment hopefully will allow me to sit back and enjoy them. But if I had to single any out, I’d go with the Ulmer double feature in July, Francis Ford Coppola’s Dementia 13 in August, and the beautiful, uncut print of Lady Frankenstein in December—a film that most U.S. audiences saw in a severely cut theatrical print.

Q: Besides the movies themselves, what else can audiences expect at Shock Theater?

MP: We’re trying to make the presentation as lively as possible. For our haunted house double feature in June, we’re presenting The House on Haunted Hill in genuine Emergo, the gimmick that William Castle used when the film premiered in 1959. We’re also in negotiations with the actual Screaming Skull to make an appearance for the film of the same name. We’ll have hosts at some of the screenings: The June double feature will be presented by the folks at the Underground Multiplex, and August features local horror-film writer Joel Wicklund of the great website Shadows and Screams. We’ll also have door prizes provided by an anonymous friend of horror films, cheap concessions, and free burial services for anyone who dies of fright.

One thing audiences should not expect—and I want to emphasize this—is a place to try out their Rifftrax routines. We’re not showing these films for people to offer lame running commentaries. We might have guest hosts, but we definitely don’t have any talking robots, even if a lot of these films were featured on Mystery Science Theater 3000. The point we’re trying to make is that if you try to watch the films on their own terms, you’ll be surprised at how good they can be. Sure, there’s going to be some moments of hilarity, but I hope audiences manage to come away with a new appreciation of the particular genius required to make good films on low budgets.

Q: What is the most difficult part of programming a series like this, or any series?

MP: Normally it’s finding prints of the movies you want to show, but Chip has taken care of that. It’s kind of a weird situation to have a plethora of things to choose from and have to narrow it down. When I was programming Bank of America Cinema, there was a more or less rigid set of boundaries, and when I booked films that transgressed those boundaries, the audience would get upset or not show up (or, in one case, try to storm the projection booth). I guess I have similar boundaries in my other ventures: CIMMfest has to be movies about music, and Shock Theater has to be scary stuff. The other difficulty, especially when you’re starting something new, is getting the word out.

Q: Why do you do it; what do you get out of it?

MP: I do it because I love movies and I love sharing my discoveries with others. I love knowing that I’ve made a big group of people happy because of the work I’m doing. I realize that I’m lucky as hell to be in a position to be doing this. If not for a particular chain of coincidences and a very supportive spouse, I’d probably be a full-time copyeditor for a dietetics journal instead of a filmmaker and film programmer. I still do the copyediting because film programming doesn’t pay unless you have that rare full-time job, but I’m thankful every day that I get to share my love of film with a bunch of people who start out as strangers but often end up as friends.