Maniac (Dwain Esper, 1934, 51 min.)

I ordinarily don’t believe in “so bad it’s good.” Most films that are lauded as classics of camp, pinnacles of putrescence, and groundbreakers of godawfulness are simply not worth watching. Certainly it’s possible to have a good time laughing at a truly awful film, but that’s time better spent watching something worthwhile. I program a series of schlocky 1950s and 1960s horror and sci-fi film, but I wouldn’t show them if I didn’t see anything of value in them.

Which makes the 1934 exploitation film Maniac such a shock, for it is a truly wretched film that I enjoyed, partly because of and partly in spite of its excessive excrescence. It’s a nasty little film aimed at the lowest, most prurient denominator, but it achieves its goals with such aplomb that I couldn’t help but applaud it. You can almost see husband-and-wife team Dwain and Hildagarde Esper cackling to themselves in front of a large chalkboard, doing lines of coke off the asses of shackled sex slaves and shouting out depravities to include in their filth-fest.

Its release is of historical note, too, as it helped me understand a little better what the Catholic Legion of Decency and other pro-censorship groups were so upset about by 1934, when the infamous Hayes Code was implemented. The harsh crackdown on cinematic prurience of any sort, imposing restrictions that took three decades to cast off, always seemed to me a bit of an overreaction. I had always chalked it up to presentism—that because I was raised in a more permissive time, I couldn’t put myself in the shoes of a 1930s viewer no matter how hard I tried. But if Maniac is any indication of the kinds of films that made it onto less-reputable movie screens, I can understand why people were so upset.

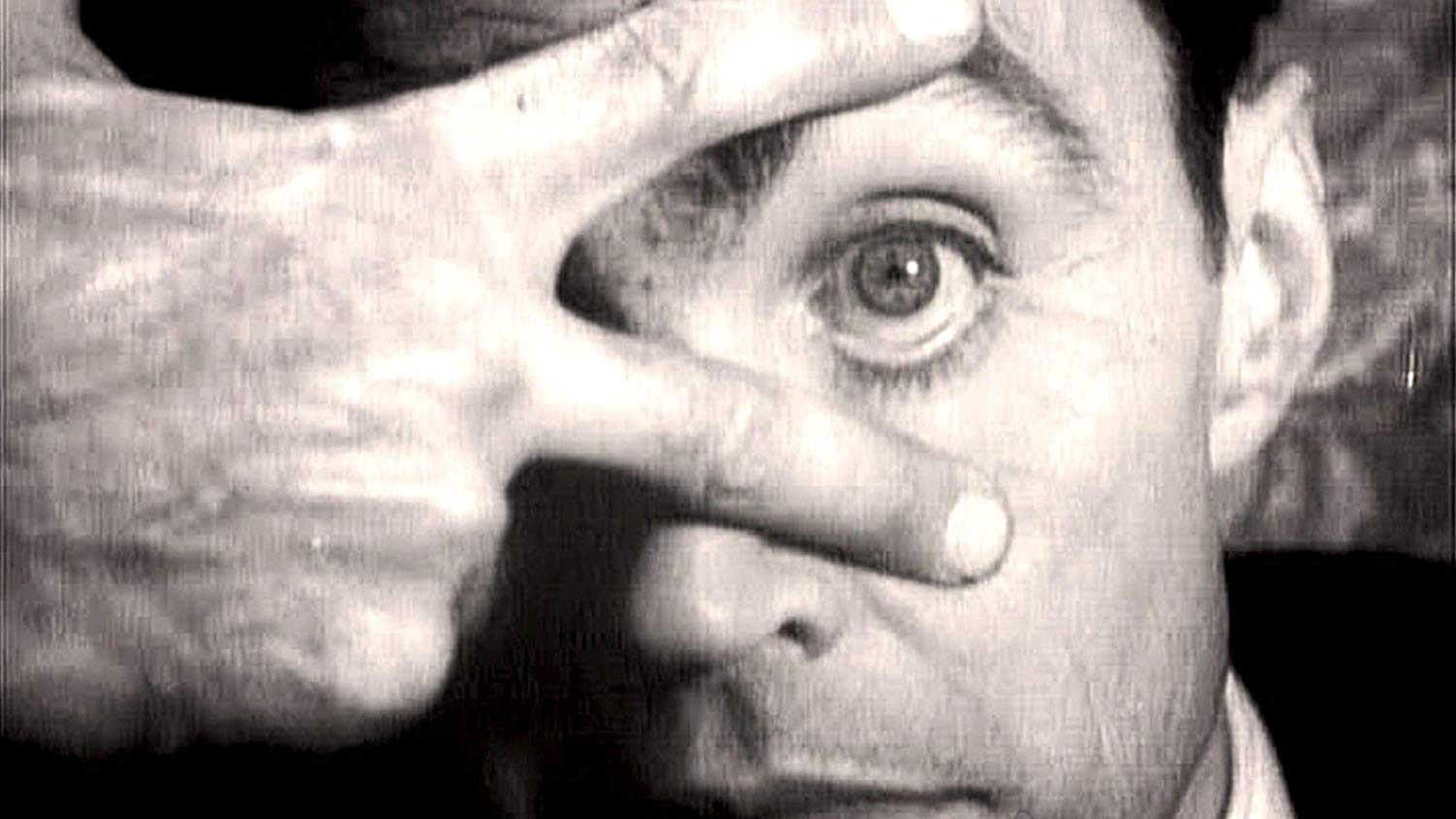

The story, if I may call it that, involves a master of disguise named Maxwell (Bill Woods) on the run from the law who takes a gig as the assistant to the mad Dr. Meirschultz (Horace Carpenter) who’s working on a serum that will raise the dead. Yes, I sort of wondered about all that too, but let’s just go with it. The doctor and Maxwell sneak into a morgue and use the serum successfully on a beautiful female corpse, but that’s not enough for Dr. Crazy. He insists that Maxwell commit suicide so that the doctor can give him a new heart and then revive him. Maxwell wisely shoots his boss, and then unwisely disguises himself as the doctor. Things start to really go wrong when he starts treating patients, and even worse when his buxom ex-wife shows up with news that Maxwell has inherited a bundle. What’s a crook disguised as a mad doctor going to do in this situation except go mad himself?

Although the film features silent-movie-style intertitles about mental illness in an effort to pass itself off as educational, it’s more interested in violence and women in various states of undress. There’s an extended sorority room scene that exists only to provide recently bathed young gals in their undies, exchanging double-entendre-laden dialogue that sometimes lacks the second entendre. After Maxwell injects one of his patients with some random potion, the patient gives the single greatest, most awful interpretation of going insane in the history of the movies—then he runs around ripping off ladies’ tops, revealing their breasts over and over. Phyllis Diller is in there (clothed!) as the patient’s wife, and she has some kind of scheme up her sleeve that never really made sense.

I felt like the film history version of Joe Bob Briggs watching Maniac, counting outrages and nipples (I lost count of both), swept away by its depravity and then shocked back into the present by its cheapness. One example: it’s clear that when Maxwell squeezes out a cat’s eye and then eats it, he’s not really squeezing out its eye, but instead the filmmakers seem to have put a glass bead into the empty eye socket of a one-eyed cat; then, in a different shot, Maxwell eats a grape or something and chortles about how it’s like eating an oyster or a grape. But dear god, the filmmakers put a glass bead into the empty eye socket of a one-eyed cat, and had their character pretend to eat it. That’s a level of dedication that I just have to respect, even though, if I believed in hell, I’d guess the filmmakers were there right now for the crimes they committed against good taste and the animal kingdom with this film. I heartily recommend watching it.