Let Me In (Mat Reeves, 2010, 110 min.)

Matt Reeves’s remake of the internationally praised Swedish vampire film Let the Right One In is an audacious undertaking. Unlike many foreign films remade in America, the original was a huge hit everywhere, including in the subtitle-phobic States. It’s also the first film in thirty years released by Hammer, the storied British film production company. I realize the connection is merely financial, resulting from a purchase of assets that happened to include a film library, but it’s a hell of a statement. It’s also a very good film, not as good as the original but able to stand on its own feet, both streamlining the material into a more traditional horror film and building up the main character’s loneliness and his need for companionship, even if it comes from a 200-year-old vampire girl.

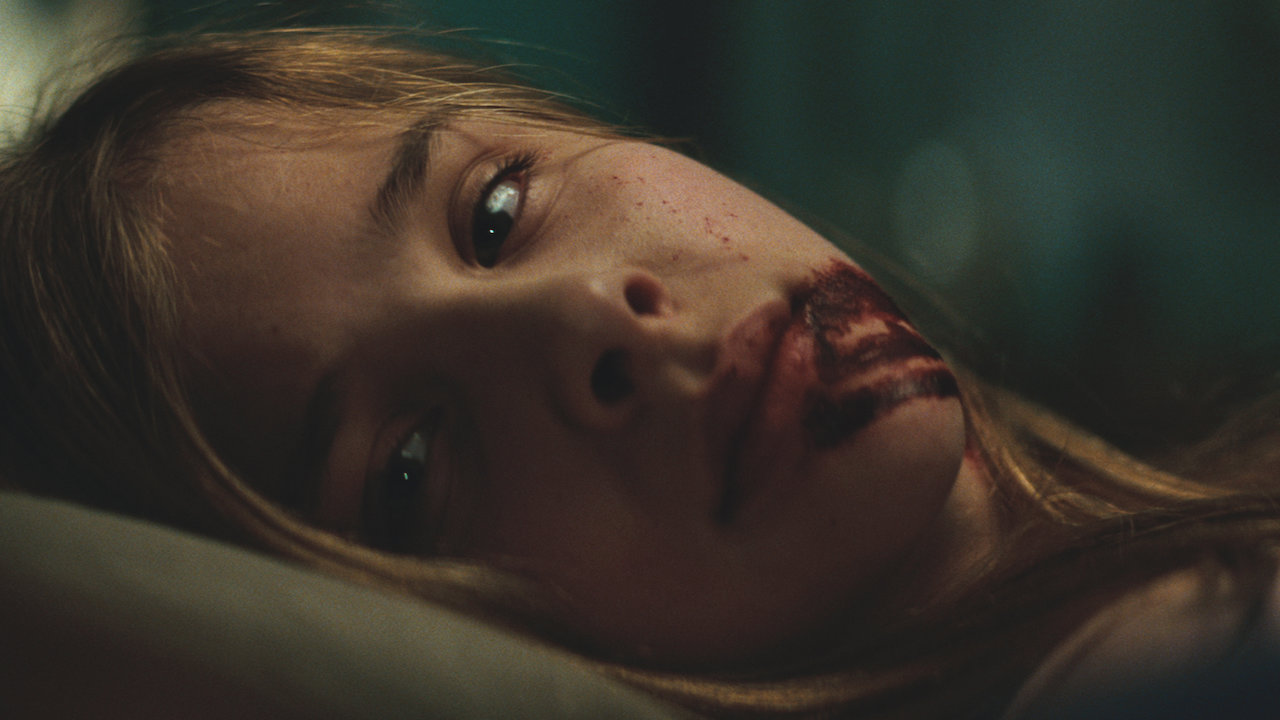

Twelve-year-old Owen (Kodi Smit-McPhee), lonely and bullied, spends a lot of time alone, either spying on his neighbors with his telescope or enacting revenge fantasies on his schoolmate tormentors in the privacy of his bedroom. One night in the frozen courtyard (Los Alamos, New Mexico receives more snow per year than Chicago!), there’s a strange girl in his territory. She smells funny, she’s not wearing any shoes, and she informs Owen that she can’t be his friend. “I didn’t want to be your friend,” he retorts, but we can see that he’s disappointed. She wasn’t serious anyway: she’s Abby (Chloe Grace Moretz), and it eventually turns out that she’s a vampire. She’s even more socially clueless than poor Owen: she can’t eat candy, she doesn’t know any of the latest songs, and she has a helper (Richard Jenkins) who murders people to bring her blood. She’s as lonely as Owen, so the two strike up a friendship, bonding over a Rubix Cube, some Now-n-Laters, and their shared loneliness. When he discovers what she is, Owen has to decide between his new friendship and a return to loneliness, and that’s not such a hard choice. Meanwhile, a sad policeman (Elias Koteas) investigates a series of murders that lead him back to Owen and Abby’s apartment complex.

Let Me In is in some ways a faithful remake, in some ways a minor reimagining (there’s no wholesale differentiation here; Reeves and co. must have decided against change for change’s sake). It both becomes more of a traditional horror film and spends more time on the budding friendship between the two lonely children, trimming away much of the fat that distracted from the central story in the Swedish original: the Father’s forays into society, the neighbor’s attempts to get to the bottom of the vampire attacks, the vampirized woman’s visit to the cathouse, and so on. Most of that is distilled into Koteas’s sad policeman, a vague, serious counterpart to Jenkins’s vague, serious murderer; the rest is merely dropped. The differences include the relocation to 1983 America, so the televisions can be full of Ronald Reagan warning us about evil and the hospitals can be lit with sickly bluish fluorescent lights without standing out as a cinematographer’s conceit. I wish Reeves hadn’t decided to have Abby move like Linda Blair post-possession, but I honestly don’t remember whether that’s an artifact from the original film. The worst thing about the remake is Michael Giacchino’s wall-to-wall score, which attempts to smother our ability to judge a scene on its own merits, but mostly fails.

The Swedish title, Let the Right One In, was an admonition, a warning about getting entangled, an extension of Eli’s statement that “we can’t be friends.” The English title, Let Me In, can be an imperative, but it can also be a desperate plea coming from either of our protagonists: Abby needs permission to enter someone’s house, but both Owen and Abby need a confessor and a protector. In the end it will be one-sided, as Owen must realize when he finds the photo-booth portrait of an unchanged Abby with a geeky kid who must have grown up to be the morose murderer played by Jenkins. But for a while neither will be alone.