Visions and Venturers (Theodore Sturgeon, 1978)

Visions and Venturers (Theodore Sturgeon, 1978)

Theodore Sturgeon (1918-1985) was an American science fiction author who is generally regarded as one of the true masters of the genre. His importance to science fiction cannot be overstated, and his influence extended beyond the page, as he coined “live long and prosper” in one of the Star Trek episodes he wrote. He is the source of the adage “Ninety percent of [science fiction] is crud, but then, ninety percent of everything is crud,” a smart riposte to critics who liked to look down their noses at his home genre. He was one of the first genre authors to include gay characters in his work, and his novel Venus Plus X (1960) remains a groundbreaking look at gender roles. Ursula K. Le Guin credited him, along with Edgar Pangborn, with convincing her that “it was possible to write worthwhile, humanly emotional stories within science fiction and fantasy,” according to Wikipedia.

That said, I haven’t read much Sturgeon, and I’m ambivalent. I think his pseudo-vampire novel Some of Your Blood (1961) is a horror classic that everyone should read, and Venus Plus X is an interesting experiment that’s worth reading but unsatisfying. I’m sure I’ve encountered some of his short stories in various collections, but nothing springs to mind. This 1978 collection, featuring stories published between 1942 and 1965, is fine. It’s fine! Nothing in it is terrible, but nothing is particularly good either. There’s a sameness to many of the stories, a structure of building mystery followed by pages of exposition, that saps the most interesting ideas of momentum.

The best of the bunch is “Talent” (1953), a throwaway about a mean kid with the ability to transform matter with his mind, but who uses it to torment animals and terrify his mom. It reminded me of the Twilight Zone episode “It’s a Good Life,” only nastier and funnier. It’s no coincidence that this is the only story that dispenses with the explanations. Other stories have interesting premises, like “The Traveling Crag,” about a fearsome weapon from another galaxy that has the side effect of turning an antisocial hick into a sci-fi Hemingway. I love the echo of Sturgeon’s famous adage about 90% of everything being crap that crops up midway through, but as with most of these stories, the last few pages consist of an overly elaborate explanation of the mystery. The worst offender is “The Touch of Your Hand” (1953), of which nearly a third is explanation.

Sturgeon’s writing is solid enough, with small flights of brilliance that tended to make me wish he had taken a bit more time revising the rest. It’s very much of its time, so every female character is introduced via bust measurements, and their characterization is solely in terms of whether the male protagonist is attracted to them or not. I don’t expect writers of the past to conform to present-day standards regarding racism and sexism, but I guess I expected something different from someone who Ursula K. Le Guin praised so highly.

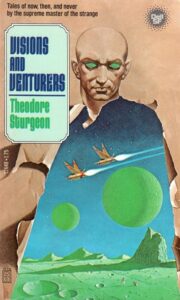

The cover, painted by Wayne Barlowe (born 1958) when he was just 20 years old, is excellent, but the interior illustrations, drawn by British artist James Odbert, are uniformly terrible.