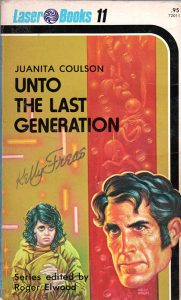

Unto the Last Generation (Juanita Coulson, 1975)

Unto the Last Generation (Juanita Coulson, 1975)

Juanita Coulson (born 1933) is an American science fiction writer who wrote sixteen novels and a bunch of short stories, was a prominent fan editor, and was one of the guiding lights of filk music—folk music about science fiction, which is a thing you should look into if you have not done so. This is the first of her novels that I’ve read, although I can see by looking through her bibliography that I once read a story she wrote set in the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons world of Ravenloft. Don’t judge me.

Unto the Last Generation, her sixth novel, is a goodnatured Children of Men in which pluck, hard work, and willingness to compromise don’t exactly save the day, but push the characters well along the road to saving it. It is mildly entertaining, sufficiently well written, and interestingly conceived. If you read a ton of science fiction in the 1970s, it would have done its job admirably but perhaps not stuck around in your brain for very long. All of this has a lot to do with the publisher, Laser Books, so you’ll have to bear with me for a digression before I get back to this particular book.

Laser Books was a Canadian science-fiction imprint from Harlequin Books (yes, that Harlequin) that published 57 novels between 1975 and 1977—a rate of three per month, all almost exactly 190 pages, which you’d receive in the mail if you subscribed to their service. The most interesting thing about them nowadays is probably that each of them featured patented big-floating-head cover art by Kelly Freas. The series was edited by Roger Elwood, who put his big stupid name on top of Freas’s art for the first thirty-odd books in the series. Elwood had made his name as an anthologist whose sheer output boggles the mind: in 1973-74, 39 Elwood-edited anthologies were put out by various publishers, or almost 25% of the new anthologies on the market during that time. And they weren’t very good anthologies. Critics—including Teresa Nielsen Hayden, who has charts—blamed him for almost single-handedly killing the anthology market by flooding it with rivers of shite. After he killed the industry, he left sci-fi and started writing religious novels.

Laser published some big names—Gordon Eklund, Jerry Pournelle, K.W. Jeter, Piers Anthony, and Dean R. Koontz under a pseudonym—but the catalog is mostly authors you probably haven’t heard of unless you’re a hardcore reader of books from this era. (It did publish quite a few books by women, which is a point in its favor.) The books were heavily, sometimes ineptly, edited, which included both rampant typos and significant bowdlerization to conform to the imprint’s strict rules: “a male protagonist, an upbeat ending, no sex or atheism, and a minimum of long words,” according to the Science Fiction Encyclopedia.

Unto the Last Generation checks off all of these boxes, although the narrator informs us several times of “urges” that our hero Parnall feels when looking at his wife; however, these urges are never acted upon, and anyway they occur within the bonds of holy matrimony so it’s all good. Laser also restricted bad language and slang, and there are some positively weird passages where Parnall chides people at length for using such innocuous slang as “chuckie” (a general address to another person, perhaps like “dude”) or “scream off” (to leave). If that’s the worst slang out there, how bad could the world really be?

I somewhat flippantly called it a goodnatured Children of Men, but I’m sticking with that. Aside from the concept of widespread human infertility leading to the downfall of society and perhaps the extinction of humanity, there are other similarities as well. These include the existence of a police state, the secretive group of scientists that’s trying to cure infertility, and the main character’s trek to shepherd the savior of humanity through a war zone. I’m not saying that P.D. James, the author of Children of Men, or Alfonso Cuarón, the writer-director of the much better film version, borrowed from this book, since it’s not the first nor the last book with a similar plot, just that it’s a useful comparison. But here, despite the fact that humanity is dying out, the tone is much less dire. The rioting Youngers, led by the charismatic trust fund kid Detloff, and the oppressive Olders, led by Parnall’s father-in-law General Grigsby, really just need to sit down and talk about things, and let science and the nuclear family save the day.

The series’s puritanism, which may have just been Elwood’s puritanism (he did leave the genre to write religious novels, after all), surfaces at odd instances in the book. It doesn’t exactly blame women for the fact that humanity is dying out, but it comes close. One female scientist blames birth control, saying “really, it started with us—with women… we succumbed to the heady thrill of being free, unfettered by our bodies, our hormones, our ova.” Thankfully (he typed sarcastically) the male scientists try to talk her down, to point out rightly that the plague had a multitude of causes, but the damage is done. There’s also a continuous hectoring tone about Parnall’s wife Therese’s decision as a young woman to pursue her career instead of having kids right away. Had she made the traditional choice, she had Parnall might have been able to have a child before the infertility crisis. But now his vigorous little sperm are frustrated, with nowhere to lodge themselves. I’m choosing to blame Elwood’s editing for this anti-feminism, but obviously Coulson was perfectly capable of retrograde attitudes too.

Aside from Freas’s fantastic (in so many senses of the word) cover art, the main reason to pick up this book is the strong resonance between that future world tearing itself apart and our own. What with the environmental catastrophes and the terrifying diseases and the oppressive governments and the general malaise as a generation faces a future that will be significantly worse than the one they were promised, there are times when it doesn’t feel like science fiction.