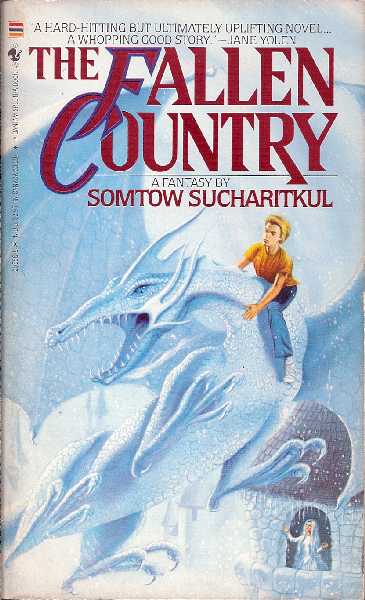

The Fallen Country (Somtow Sucharitkul, 1986)

The Fallen Country (Somtow Sucharitkul, 1986)

Somtow Sucharitkul (born 1952), aka S.P. Somtow, is a Thai polymath who started out as an avant garde musician in the 1970s, became a respected science fiction writer in the late 1970s, helped create the splatterpunk subgenre of horror in the early 1980s, and later returned to music. He’s currently the director of the Bangkok Opera, which he founded. He’s one of my favorite authors, one of the great, if unheralded, masters of any genre he cares to attempt.

This story first appeared as a novelette in a 1982 collection called Elsewhere, Vol. II, and Somtow expanded it into a novel in 1986. He adapted the original 1982 story into an opera called The Snow Dragon, which premiered at Milwaukee’s Skylight Music Theatre in 2015. (I was there.)

When Billy Binder appears one day, nearly frozen to death and clinging to the church belfry in the middle of a Florida heatwave, he’s reluctantly befriended by a teenager named Charley. Billy’s only escape from his mother’s abusive boyfriend Stark is into the Fallen Country, a snowbound world where the cold numbs the emotions of its inhabitants until they’re little more than zombies, and Billy rides a snow dragon to save beautiful princesses and vanquish monsters. Stark is here, too, as the evil Ringmaster, his lion tamer’s whip scarring the sky and cutting the flesh of Billy’s dragon guide.

Of course it’s an imaginary world, right? The kind that abused kids take refuge in, a place where they have power, where they can fight back. But Billy’s alternate reality is real, as Charley is forced to acknowledge when he’s swept into the Fallen Country to help Billy in his quest to vanquish the Ringmaster. Billy has power here—his anger—and he decides that he can put a stop to Stark’s reign of terror.

I believe this was marketed as young adult fantasy, and it’s dark as hell. Billy suffers horrific abuse at Stark’s hands, physical and possibly sexual, and the system either can or will do nothing about it. It’s graphic and regular, and it’s a little hard to take. There’s also some inappropriate flirting between Charley and Dora, the hapless school counselor who tries to convince Billy that the Fallen Country isn’t real.

Someone at the Washington Post (I’ve been unable to ascertain who said it) said that “Sucharitkul can create a world with less apparent effort than some writers devote to creating a small room.” That’s true, and not true at the same time. Yes, he can create a world in a couple of paragraphs: the Fallen Country feels like a real place as soon as we enter it, perhaps because Somtow has a staggering recall of the myths and legends of several cultures, and he can employ shortcuts without them seeming like shortcuts, or perhaps because he’s a fantastic writer. Probably both.

But when shortcuts appear in the mundane world of Boca Blanca, Florida, it’s more obvious: characters are sometimes distressingly wooden (Dora the counselor seems less like a person than a mouthpiece for generations of bad child psychology), and scenes that aren’t about Billy and his trauma feel rushed, like Somtow was impatient to get to what he came here to write about.

It’s still a great and valuable novel despite these complaints because nobody writes better than Somtow when he’s in the zone. The complex relationship of Billy and Stark is so painfully real that I found myself weeping, having grown up not in the Fallen Country but perhaps somewhere on the outskirts. Somtow’s insight into the tools kids use to overcome abuse is clear and compelling, and he does a fantastic job balancing the requirements of a fantasy novel and the dead serious subject matter he’s addressing. In the best possible way, this is literature about escape and healing that functions as an escape and as a tool for healing.