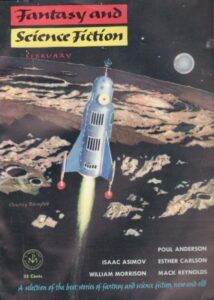

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, February 1954

“Playground” by William Morrison

Look, I don’t expect early sci-fi to be progressive by today’s standards (although sci-fi has always been more progressive than society at large), but even by the standards of 1954, this story is shockingly sexist. A family on an interplanetary vacation takes a rest stop on a planet that turns out to be inhabited by giant aliens. Part of the charm, I guess, is that it takes the family a while to figure out what’s up: that the giant trees they encounter are blades of grass, that the deafening sounds are voices of another harried giant alien family. But that’s the extent of the charm. The story opens with a woman named Sarina piloting the family spaceship while her husband George reads “a book of old poetry, the kind that rhymed,” but that’s the end of egalitarianism. George, whose POV we unfortunately inhabit, is constantly annoyed at his spouse and children, keeping up an internal monologue of disparaging comments about his family and the alien family they encounter. It’s like an unfunny episode of The Honeymooners. Morrison (real name Joseph Samachson) was a biochemist who wrote a few dozen sci-fi stories and helmed F&SF’s science column in 1957 and 1958.

“Somewhere East of Rudyard” by Esther Carlson

Hey, just because a person is a woman doesn’t mean she can’t be sexist. Esther Carlson’s story is just six pages of cringe-inducing elements: in the first line, a woman is described as “rather beefy” and having a “mannish haircut”; the story is about an adventurer who’s been cursed because he stole a ruby from an idol in an unnamed (African?) country; and it’s supposed to be funny. I am generally allergic to sci-fi humor, with exceptions. Carlson was a friend of James Baldwin and Richard Wright who published one novel and several stories in different genres.

“℅ Mr. Makepeace” by Peter Phillips

OK, I mentioned exceptions. This droll little story, a satire of middle-class British manners and bureaucracy, is about a proper gentleman named Makepeace who keeps getting letters addressed to “E. Grabcheek, Esq., ℅ Tristram Makepeace.” He attempts to return it, but since it’s properly addressed to him, the postal carrier, and then higher and higher levels of the postal service bureaucracy, refuse to do anything about it. Makepeace is too much the gentleman to open the letter himself, and he suffers a psychotic break while trying to solve the problem of the letters. It’s positively Kafka-esque, but with a bit of Monty Python cheek to it. Phillips is best known for writing an early virtual reality story, “Dreams Are Sacred,” which has been anthologized dozens of times.

“The Other Alternative” by Mack Reynolds

Other Alternatives Inc. offers its clients two services: privacy, and the opportunity to travel to alternate pasts and murder people. “Mr. Smith” drops by with a strong desire to kill Billy the Kid, and the company is happy to oblige. There’s a ton of psychobabble about feelings of inadequacy leading to a desire to murder 19th century gunmen. I like the twist at the end, when the foolproof system fails and Pat Garrett ends up in the Other Alternatives office. But overall this is a head-scratcher of a story because there’s not really much to it.

“Arrangement in Green” by Doris Gilbert

Joe Brand, a down-on-his-luck expressionist painter figures out how to commit suicide and transfer his soul into the body of an influential art dealer, and from there turns his now-deceased former self into a cause celebre through a savvy marketing campaign. It’s a fantastic concept, and for the most part Bland handles it well. There’s a bit too much mid-1950s disparagement of abstract art, but that was par for the course in 1954. And she wraps up the story beautifully as now-Bland tries to capitalize on his newfound fame by painting more pictures but realizes that he can’t. Gilbert published only two sci-fi stories, and it’s a damn shame, because this was quality work. She’s better known as a screenwriter working for B-movie studio Republic Pictures and various television shows including Science Fiction Theater.

“The Miracle of the Broom Closet” by W. Norbet (Norbert Wiener)

This is just bad. A mostly expository story about strange happenings at an Anglo-run lab located in Mexico, it has to do with tests done at that lab whose results cannot be replicated elsewhere. It turns out that the Mexican janitor had been praying to Saint Sebastian to make the tests successful. And that’s it, all recounted the way you’d write about it in a letter to your mom. Wiener’s talents lay in the field of computer science, where he’s considered the father of cybernetics; this was one of two fiction stories he wrote, and for good reason.

“Sanctuary” by Daniel F. Galouye

Hoo boy, this story makes this magazine worth hunting down. Galouye tells the story of a young woman who can hear other people’s thoughts who journeys from rural isolation into New York to seek help from a mysterious institute. But the city is a nightmare: she’s bombarded with waves of anxiety and pain and ill-intent from the thoughts of the millions of people around her. Galouye buries the reader in this onslaught, highlighting the threats of sexual violence from men, including at least one stalker. The end result is a paranoia-inducing nightmare in which even the putatively happy ending comes laden with suspicion and fear. I really need to check out Galouye’s novels, especially Simulacron 3, the basis for Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s World on a Wire.

“The Appraiser” by Doris Pitkin Buck

A wee bit of a story about a guy who’s bargaining with Satan over the price of his soul. He wants riches and a beautiful ballerina, but the market has dropped out and the best Satan can do is a decent income and an affair with a secretary. It’s cute, I guess, but there’s not much to it. Buck was a stage actress before embarking on a sci-fi career at the age of 54. She published a couple dozen stories (this was her second publication) and poems and was one of the founding members of the Science Fiction Writers of America.

“Call Me Adam” by Winston Marks

Oh, this one was fun. The Adam of the title is a highly evolved protozoan, coaxed into human form by a sadistic scientist. Adam is pretty smart for a protozoan, and once he offs the scientist, he takes his place as a university professor. There’s a lot of fun in Adam’s poker-faced recitation of the scientist’s depredations, and Marks brings an understated sense of humor to what the magazine editors pointed out was a hoary concept by 1954. Marks published almost fifty sci-fi stories between the 1940s and 1960s. If this one is any indication, he’s an underappreciated talent. Project Gutenberg has released e-book versions of many of his works.

“The Immortal Game” by Poul Anderson

Snoozefest. Anderson turns a famous chess game into a sort of non-story, a concept that was done much better by my great aunt in law Dahlov Ipcar in her 1969 novel The Warlock of Night. I had a hard time finishing this. It’s baffling to me that it’s been anthologized so many times.

“The Fun They Had” by Isaac Asimov

A slight story for kids, “The Fun They Had” is about a far future where children are educated in isolation by computers. A young girl finds an actual book in her attic, her only friend dismisses the find because books-on-screen are so much better, and the girl wishes she had lived in an earlier era when school meant education but also socialization. It’s cute, but there’s not much to it.