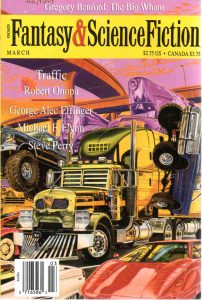

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1995

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1995

Editorial

Editor Kristine Kathryn Rusch outlines the results of a survey of readers about the state of the magazine. Interesting tidbits: 55% of readers wanted less horror, and Rusch agrees that she’s tired of it—an interesting reflection of the rapid deflating of the horror bubble of the 1980s and 1990s. And people prefer short stories to longer forms, which is the correct stance. Fifteen percent don’t read the nonfiction columns, which is also the correct stance.

Michael Flynn, “The Promise of God”

Seven-time Hugo Award nominee Michael Flynn crafts an interesting but scattershot picture of a post-apocalyptic world where humans have reverted to the middle ages, and some people are born with magical powers, perhaps due to genetic mutations—there are hints of mutant populations dwelling in the Barrens, but Flynn doesn’t get into them much.

Our protagonist is Nealy, a young man with the ability to do magic, known as “the Other Way,” and we meet him as a young woman propositions him: if he makes it so she and her husband become immune to lice, she’ll have sex with him. Their arrangement is interrupted by the arrival of Greta, Nealy’s older “house bound,” sometimes called “goodwif,” which Flynn uses interchangeably to mean romantic partner. Greta points out that washing one’s clothes and person are a good way to prevent lice, and Agnes, scandalized, leaves.

Flynn’s depiction of gender issues is the main point of interest here. First, he deftly explains this society’s way of dealing with magically gifted youth—they’re bound to a rixler, an older person of (usually) the opposite sex, whose “instruments are the knout and the caress,” who trains them in proper use of magic, as well as becoming the magician’s lover. There’s an interesting blurring of traditional gender: both men and women are referred to as men, both men and women can be goodwifs, and the master magician who takes Nealy away from his parents asks them whether he prefers boys or girls.

Book Reviews by John Kessel

I don’t read the book reviews.

Books to Look For by Charles de Lint

I don’t read the book reviews.

Steve Perry, “Just Ask”

Steve Perry, a kitchen sink novelist—in that he writes just about everything, from TV show novelizations to Conan pastiches in addition to original novels—delivers a short, “funny” trifle, and I should mention that I generally don’t like funny sci-fi outside of Douglas Adams. Anyway, it’s about a man who lives in an upscale Republican neighborhood who spends every day painting his house blue—“a nice warm blue, with a little gray”—but every night, the house reverts to yellow— “more of a sand color, manila maybe.” He sets up cameras, he camps out on the lawn, but every morning, it’s yellow. The punchline—and it is a punchline, because the story feels like nothing more than a joke stretched to 11 pages—is cute, but overall I am scratching my head over why the editors thought this was worth publishing in the most prestigious sci-fi magazine ever

Sally Caves, “Ketamine”

Sally Caves is the pen name of English professor Sarah Higley, who is perhaps best known in sci-fi circles for creating the engineer Reginald Barclay in Star Trek: The Next Generation, but she’s also written extensively about medieval languages and literature and about science fiction, and by the by she created a constructed language spoken by polydactyl humanoids who worship cats. Honestly, she seems like someone I wish I could hang out with—one of the “good academics,” which I define as an academic who can and will talk to a stranger at a party about something other than their research. (As a faculty spouse, I can assure you that most academics [and most people] are not good academics.)

Anyway.

Leda is fiercely allergic to her polydactyl kitten Mia, who may be turning into a human girl, or that may be a manifestation of Leda’s unspecified mental illness, symptoms of which include twitching and other involuntary movements, obsessive hair removal, and breaks with reality that may be dreams, or waking dreams, or hallucinations.

Caves tackles so much in this story: philosophical debates over whether animals have consciousness, systemic societal misogyny, how adorable cats’ toe beans are. I just now processed the protagonist’s name, Leda, and its connection to another famous story of animal transformation. Bravo, Dr. Caves.

This is a fantastic story, unique and beautifully crafted, the kind that makes you open the Internet Speculative Fiction Database so you can find more to read by her, only to discover to your horror that she’s published only three science fiction stories, and none since 1999. That’s a damn shame.

Robert Onopa, “Traffic”

Another story by an English professor, this one about the worst traffic jam in history. In a future where gridlock has blossomed to the point where people spend days trying to drive across Los Angeles, where leaving the main roads can get you killed, a parking lot attendant takes an unauthorized turn and enters the world of Nomads, a sort of blend of Romani travellers, Native Americans, and undocumented immigrants who survive by ferrying cargo across the country in caravans that never stop moving. Shades of Heinlein’s “The Roads Must Roll,” with a different take on labor.

The world-building is stellar, even though it stretches believability—Americans love their cars, but we already know that when traffic gets bad enough, people start finding alternate routes or stop driving in favor of public transportation. But Onopa brings his Nomads to vivid life, sketching in their lifestyles while paying homage to his native Chicago, which is the closest place to Los Angeles that the narrator can re-enter the legal traffic pattern. His depiction of an attack by roving gangs of bandits driving monster trucks was particularly fun.

Film Reviews by Kathi Maio

I seldom read the movie reviews unless I’m looking to see how wrongheaded they are. My unscientific and spotty survey indicates that most of the movie reviewers are not very good, starting with Baird Searles and continuing through Harlan Ellison, who was brilliant but also frequently wrong about movies. Anyway, Maio doesn’t like the Jean-Claude Van Damme film Timecop (which is the correct take) or the Brandon Lee starrer The Crow (which, honestly, is mostly correct too).

Gregory Benford, A Scientist’s Notebook

I don’t read the science column.

George Alec Effinger, “Maureen Birnbaum at the Looming Awfulness”

I don’t do comedic sci-fi and fantasy. Aside from Peter S. Beagle and Douglas Adams, most of it is incredibly unfunny. The editors of this esteemed journal were fond of it, so these issues are scattered like rabbit droppings with “funny” stories by Ron Goulart and Reginald Bretnor. To that list I must add Effinger, who, as I understand it, is not normally funny—wait, I mean does not ordinarily try to be funny, as this story is also not funny, but unintentionally so. And it’s a series that I guess I must look forward to encountering again. Good god. Anyway, a sort of 1990s Valley Girl type who can travel through time encounters Lovecraftian horrors. Like, as if.

Leonard Rysdyk, “The Holo Man”

Interesting story by another author whose output was limited to a few stories. In this case, Rysdyk was also a reviewer for The New York Review of Science Fiction, which today I learned existed at all. But the late great David Hartwell edited it, so it has to be good.

The narrator is a scientist stationed on a distant planet who interacts with the world primarily through virtual reality—a complex system of robots who feed sensory input to the user. It’s perfect for exploring inhospitable planets, and also for boinking. VR tourists can pay to experience the feeling of discovering a new plant species, or can have torrid and realistic affairs with the “rangers” who staff these interplanetary output. Our narrator falls for a mysterious woman who begs him to move back to Earth to be with her. The buildup is really interesting; the payoff, not so much.