Joanna Russ vs. the Sossidge Factory

Joanna Russ vs. the Sossidge Factory

Joanna Russ was the best science fiction critic in history. Full stop. A radical feminist in a genre dominated by men, she revolutionized sci-fi criticism in her reviews in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which appeared between 1967 and 1980. Her columns are a joy—I hardly ever read the nonfiction columns in this magazine (book reviews, science, movie reviews), but I seek out hers for their incisive wit, incendiary takedowns, and breadth of references. She seems to have read everything, and she put it to work in her columns. But she could be scathing: as James Tiptree Jr. wrote to her, “Do you imagine that anyone with half a functional neuron can read your work and not have his fingers smoked by the bitter, multi-layered anger in it? It smells and smoulders like a volcano buried so long and deadly it is just beginning to wonder if it can explode.”

In 1975, she made an offhand, hilarious comment about Robert Silverberg, and this is an admittedly obsessive, digressive, and pointless history of that situation.

She was ahead of the curve in so many ways, and here’s one: Every so often, someone tweets a parody of male writers’ sexualized descriptions of female characters, usually in the form of a sexualized description of a man. It’s quite possible that Russ invented that trope: in the December 1972 issue, she writes that she’s working on a novel in which all the men are characterized as follows:

He was a medium-sized man with round buttocks and lumpy testicles, one longer than the other. They swayed as he walked. Sometimes they swayed freely. His penis hung down in front. I decided to take him on those terms.

Her reviews often provide insight beyond the particular book she’s reviewing. Writing about Kate Wilhelm’s excellent novel Let the Fire Fall in the September 1969 issue, she said “The book is written in a style Henry James (in another context) once called ‘feminine’: that is, the accents never fall where you expect them to, the ‘big’ events are over in a flash or are revealed obliquely, and the novel always presses on to something else.” This made me revisit moments in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea novels, as well as the protagonist’s encounter with her witch mother in Jo Walton’s Among Others, and it put into words my inchoate reactions to those books.

I would be lying if I didn’t admit that it’s her hit pieces that give me the most pleasure, even when I don’t necessarily agree with them. She wasn’t afraid to go after the heavy hitters of the genre, either. In April 1969, she wrote “Frank Herbert is an interesting writer, or perhaps I should say an interesting phenomenon, for both Dune and The Santaroga Barrier are not first-rate books, but carefully worked up third-rate ones. The exhaustive care with which the working up is done deserves praise, but many a reader of Dune has thought himself responding to the profundity of an elemental vision of life when what really got him was a combination of reckless exoticism, flamboyantly impossible social conditions, sheer thoroughness, and what I can most politely call megalomania.” That’s fair.

She could be hilarious in her takedowns: after excoriating John Boyd’s debut novel The Last Starship from Earth for a long paragraph in the September 1969 issue, she says “I forgive Mr. Boyd for the anguish this novel caused me and hope he will eventually forgive me the anguish this review may cause him, but for Berkley [the publisher], there is no forgiveness. Only reform. Don’t do it again.”

And she could turn what sounds like harsh criticism into the highest of praise, as she did with Ray Bradbury in the July 1970 issue.

Ray Bradbury does everything wrong. Anne McCaffrey can sing better; Poul Anderson can think him under the table; and compared with Brian Aldiss, he is as a little child. To him old people are merely children, in fact everybody is a child; he prefers imitative magic to science (which he does not understand); his morality is purely conventional (when it exists at all); his sentiment slops over into sentimentality; he repeats himself inexcusably; he makes art and public figures into idols; and there is no writer I despise more when I measure my mind against his, as George Bernard Shaw once said of Shakespeare.… Art can exist without encyclopedic knowledge, sophisticated morality, philosophy, political thought, scientific opinion, reflection, breadth, variety, and a lot of other good things. What else can I say? Mr. Bradbury strikes me as a writer on the same level as Poe, the kind of writer people will still be reading, still downgrading, still praising a century from now.

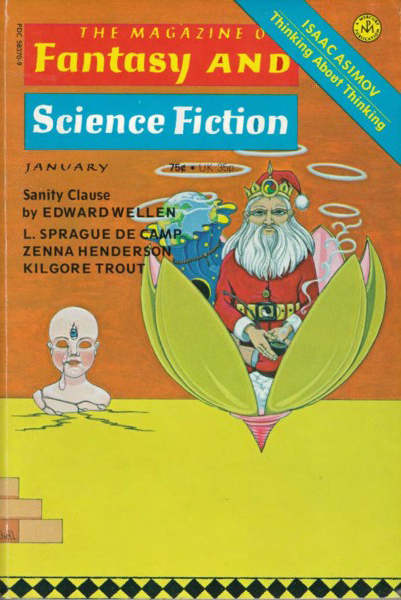

But I digress. This is supposed to be about her critical relationship with Robert Silverberg, a series of miniature struggles with his books and his growth as a writer. It all exploded in the January 1975 issue where, reviewing Silverberg’s latest book Born with the Dead, she said “Robert Silverberg is a sossidge-factory trying to become an artist. To my mind he’s done so only twice.” (Note that the title novella, “Born with the Dead,” won the Nebula Award for Best Novella, a fact that does not prove Silverberg’s status as an artist, but suggests that others thought him such.) Then in March 1975, she took another shot at him: in a review of a collection called Stellar 1, she says that Silverberg’s story “Schwartz Between the Galaxies” is where “Silverberg becomes an artist for the second time in his life,” the very definition of damning with faint praise.

Russ wasn’t down on Silverberg as a rule, and there are signs that she held him to a higher standard because he was at least a contender for the title of Artist. Her July 1973 review of Dying Inside calls it “interesting but not moving” and admits that “I’m just not on its wavelength.” She says “the solidity of it is beyond question, as is the quality,” and praises it for being “the first time Mr. Silverberg has used his extraordinary wit in print.” In the same column, reviewing an anthology he appears in, she calls him “formidable.”

She had already discussed her changing assessment of him. In April 1971, she characterized pre-1967 Silverberg as an “extremely self-conscious and clever hack…. Old Silverberg is an idiot, but New Silverberg is something else: a highly colored, gloomy, melodramatic, morally allegorical writer who luxuriates in lush description and has a real love of calamity.”

But now he was a sossidge-factory trying to become an artist. Which seems mean. Fireworks, of a minor sort, ensued.

In the April 1975 edition, which coincidentally features the first part of Silverberg’s The Stochastic Man, Russ offers a mea culpa:

I committed the kind of blooper about Born with the Dead that has made me wish I were dead. I didn’t say what I meant. I called the book’s extremely talented writer “a sossidge-factory trying to become an artist, assuming that everybody knew Mr. Silverberg’s factory days ended fifteen years ago and that by “artist” I meant work so faultless and fully realized that one would not wish a word of it changed. Then I went and did it again, reviewing Stellar I. I wish to apologize publicly for my fumble. Silverberg is a very-ex-sossidge-factory still in the process of developing as an artist.

She goes on to praise two of his recent stories as “absolutely satisfying works, without reservations, the kind of fully-fused writing that’s rare in any writer’s career.”

In the same edition, F&SF editor Edward L. Ferman launched a letters column, perhaps because of two particularly juicy feuds: Kurt Vonnegut vs. Kilgore Trout (more on that in a future article) and writers vs. Joanna Russ. Barry Malzberg spoke up for Silverberg. After praising Russ for her “fair and enlightened perspective which comes from something more than an acquaintance with modern literary tradition and its roots,” he lambastes her “appalling” characterization of Silverberg as a sossidge factory. Russ’s comment is “unfair on the face of it—I think the man is an artist—but even more seriously is a denial of the agonizing efforts that this writer has made over the years to bring his work to an achieved literary standard…. If Joanna Russ cannot make the distinction between the level of intention and execution in Born with the Dead and that of [a James Gunn novel, Cave of Night, which Malzberg views as much inferior] then what is Silverberg to do? … Why should he bother? Why should any of us bother?”

Old-school pulp writer Charles Runyon weighed in with a letter in the September 1975 issue: “I’m sure a lot of us old sossidge-factory hands suffer ambivalent feelings about Silverberg. We would like to believe that one of our number has clawed his way up from Hacksville and attained the exalted status of Literateur…. At the same time we are reluctant to admit it can be done—otherwise we’ll have to come up with an excuse for not doing it ourselves.” He was unhappy with both Russ and Malzberg: “I will say in closing that I regard with glazed eyeball the Protectionist tendency which Joanna shares with the aforementioned Barry M. Both report motivations of love while rapping others sharply about the head and shoulders for treading upon the sacred sod of science fiction. To borrow a phrase from Kilgore Trout: ‘This is bulshit.’”

Perhaps proving Russ’s point, and predicting the rise of the Sad Puppies controversy of the 2010s, a reader wrote to complain about Russ: “I’d like to see some male chauvinist pigs reviewing books in the future. Miz Russ is too militantly female for me.”

It is perhaps a coincidence that Russ disappeared from the book review column until November 1976, more than a year and a half after her apology. (Her most famous novel, The Female Man, was published in February 1975, so perhaps she was just busy.) Avram Davidson wrote the reviews in the May 1975 issue, there weren’t any for June 1975, and then Richard Delap, a fan writer and editor, took over. Russ came back, but only for five more review columns before departing for good in 1980. And the cover story of her last issue as book reviewer? “Lord Valentine’s Castle” by Robert Silverberg.