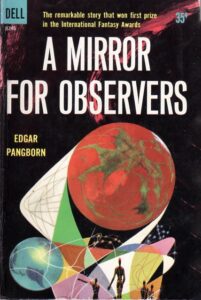

A Mirror for Observers (Edgar Pangborn, 1954)

A Mirror for Observers (Edgar Pangborn, 1954)

Edgar Pangborn (1909-1976) was an American science fiction writer who is mostly forgotten today, remembered, if at all, for his 1964 novel Davy, which was nominated for a Hugo. Judging from this gorgeous, melancholy little book, he deserves rediscovery, as his work compares favorably to that of Ray Bradbury, the writer who kept popping into my mind as I read Pangborn’s prose. I learned that Ursula K. Le Guin credits Pangborn and Theodore Sturgeon for convincing her that it was possible to write worthwhile, human fantasy and science fiction stories. That’s the highest praise I can imagine.

A Mirror for Observers follows two Martians, called Salvayans here: an Observer named Elmis and an Abdicator named Namir. Observers watch, and sometimes help, humanity in their long, difficult crawl toward enlightenment, and Abdicators believe that humans are inherently corrupt, and seek to help them in their long, difficult crawl toward self-annihilation. The pair sets their sights on Angelo, a twelve-year-old boy living in a decaying industrial town in 1963—or 30,963, as the Salvayans have been watching humanity for thousands of years. Elmis becomes Angelo’s friend, and Namir and his son attempt to corrupt the boy. Angelo disappears after a tragedy, and when Elmis finds him again nine years later, he’s involved with a fascist political party, and the future of humanity is in danger. Along for the ride is Sharon, a young piano prodigy who is in love with Angelo, and who re-enters his life when Elmis finally tracks him down. (As an aside, Pangborn was a talented pianist, and several pages are devoted to a concert given by Sharon that stands among the best descriptions of music in genre fiction—I can think of only The Vampire Tapestry by Susy McKee Charnas and of Somtow Sucharitkul’s Vampire Junction novels as equals to Pangborn’s ability to convey music through prose well enough to make me hear it, even though the pieces were unfamiliar to me.)

One of the greatest strengths of this mysterious book is that it’s unclear why they chose Angelo. Late in the novel we learn, after a fashion. Basically, Angelo is a bright kid with perhaps some greater than usual insight: “In Angelo there was and remains a blend of intelligence, curiosity, courage, and good will” (p. 149). Elmis wants to support him, to ensure that he “reaches maturity without disaster,” so he can apply that blend to the betterment of humanity, be it through art, politics, teaching, whatever. The method doesn’t matter. Namir wants to corrupt him, because any steps toward enlightenment are false in his mind.

Elmis struggles constantly with his mission, an Observer who meddles in ways that he’s unsure are right. “By what right do we intrude on [Angelo’s] or any other life? No right at all, since ‘right’ in this case would imply the existence of a superworldly authority dispensing privileges and prohibitions. We Salvayans are agnostics born. Having neither belief nor dogmatic disbelief in any such authority, we interfere in human affairs simply because we can; because, conceitedly or humbly, we hope to promote human good and diminish human evil, so far as we ourselves can know good and evil. How far is that?”

The mirror of the title is an ancient Minoan bronze that, through some defect or genius of craftsmanship, shows the viewer different aspects of himself—future selves, frightened selves, selves that may or may not be. “Some subtle distortion in the bronze that compels many truths to cry aloud.” Viewing one’s reflection in the mirror can cause distress, because “it is one thing to know, with the mind only, that one will be old, that one has different faces for victory, shame, death, hope, defeat; another thing to watch it brilliant in the bronze.” The mirror is brought out only twice in the story, plus once in a painting by Angelo, but it’s a central metaphor for the struggle for the future of humanity between Elmis and Namir.

I compared Pangborn favorably to Bradbury, and I stand by that. I will admit to dog-earing several dozen pages as reminders to save some of his achingly beautiful prose. Here’s a sunrise: “Sunrise was gradual and deep this morning. I sat by one of my living room windows and saw the grayness above the East River take on a slow flush and then a hint of gold. Spires and rooftops on the Brooklyn side were catching hold of light like cobwebs on the grass after a rain. I watched a tug slip across the river on some errand clothed in magic by the latter end of night. It drew a soft line of smoke on the water, for there was a small breeze out of the east. The line broadened to a pathway, white and gold at my end, total mystery beyond.”

A Mirror for Observers is a lovely, hopeful masterpiece of humanist science fiction, light on science but rich with gorgeously written, thoughtful debates over the nature of humanity itself. “Tonight I am racked by an old malady, a love for the human race,” Elmis writes to his supervisor (the novel is written as his official report to his superiors), and Pangborn obviously shares that love.