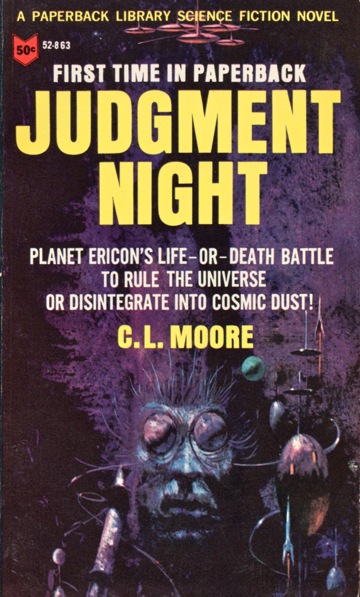

Judgment Night (C.L. Moore, 1952)

Judgment Night (C.L. Moore, 1952)

C.L. Moore (1911-1987) was an established science fiction writer even before she married Henry Kuttner in 1940–he had written her a fan letter in 1936, thinking she was a man. Writing together as Lewis Padgett, the two of them became something special, blending their unique talents to produce several memorable works, most notably the frequently anthologized story “Mimsey Were the Borogoves.” The pair sometimes worked together and sometimes pursued their own projects, and this novel grew out of a novella Moore published in John W. Campbell Jr.’s Astounding Science Fiction in August and September 1943. After Kuttner died in 1958, Moore retired from writing, which is a damn shame.

In addition to being a superior space opera, Judgment Night (my first solo Moore novel) is worth reading for two reasons: a nascent feminism, sort of, that Moore wrestles with throughout the narrative, and a truly amazing action sequence that comprises the final two-thirds of the book’s slim 150 pages.

First, the feminism. There’s a fascinating scene near the beginning that I think outlines the difference between what a woman writer was capable of and what a man might have written. Juille, the self-described Amazon who is the head of her empire’s military, is getting dressed for a night of intrigue in the floating pleasure planetoid Cyrille. What makes this special is that instead of being a kind of “the cloth draped breastily over her ample bosoms” ogling situation that a man might have written, or might still write, it’s a frank examination of the psychological implications of differences in masculine and feminine dress. Juille is very conflicted about abandoning the military uniform she’s worn since she was a child in favor of traditionally feminine garb, and Moore analyzes the defenselessness that a gown implies (Juille has to abandon her weapons, armor, and pants). That analysis carries through Juille’s love/hate/attempted murder relationship with Egide, whom she at first doesn’t realize is an enemy who intends to assassinate her. Moore constantly reminds us of what many women even today go through when starting a relationship with a man who is essentially a stranger: gosh, this guy is handsome and sweet and romantic, but I don’t know whether he’s going to suddenly hurt me physically.

It’s not entirely free of outmoded gender beliefs, of course: Egide’s “sensuous mouth” (Juille/Moore are obsessed with the guy’s sensuous mouth) and sartorial choices, including a flowing red cloak and a form-fitting outfit made of what appears to be living fur, lead Juillle to believe he’s less manly–certainly less manly than another character, “the very essence of all warm, human masculinity,” who turns out to be an android, suggesting some interesting thought exercises. But even this is part of Juille’s cross-examination of her own deeply held and culturally indoctrinated ideas about femininity and masculinity, and it’s definitely light-years ahead of what you’d expect from the genre in this period (or, honestly, most genres during most periods).

Then, the action. A third of the way through the novel, Moore embarks on a stupendous, hundred-page action sequence that beggars description. From the catacombs of ruined empires beneath the Lyonese palace to the wreckage of Cyrille, changed from a pleasure planetoid into a labyrinthine hellscape, Juille evades Egide and his gargantuan countryman Jair in a chase that I’d call cat-and-mouse if cat-and-mouse involved considerable wanton destruction. I was stunned, and I stayed up way past my bedtime to finish it. Moore’s descriptions of Cyrille being smashed to bits are especially evocative here, as the three-dimensional computer-generated people and settings that were intended to fulfill rich visitors’ every wish start to malfunction, morphing into nightmare creatures and idyllic vistas interrupted by broken girders and smoking tangles of wires.

Moore is a master of pacing, and although I called it a single sequence, it’s in fact two. It’s divided (so readers can take a breath) by Juille and Egide’s separate visits to the oracle of the gods of Ericon, in which Moore reminds us about the real lessons of history and the undependable advice of oracles and signs (and also how you should always be nice to catlike creatures even if they have more than four limbs). Then it’s off to the races again, culminating in a moody, absolutely perfect ending.

Along the way are absolutely beautiful moments where Moore flexes her imagination and command of the English language. My favorite was a scene in which Egide, who carries a harp slung across his back like some kind of hipster satyr, strums a note in a room full of ancient weapons that resonate with his music like the ghosts of a dead orchestra of destruction, one of many instances in which humans demonstrate their inability to take a hint. Not knowing Moore’s other novels, I can’t say whether this is the best place to start with her, but fans of the golden age of science fiction can’t go wrong with this one.