Hardware (Richard Stanley, 1990, 85 min.)

Richard Stanley’s little-seen debut film presents a society bent on self-destruction via any means possible. In the middle of a typical-looking post-apocalyptic world filled with tossed-off dialog about radiation levels and mutations, there’s something darker at work, a wholesale assault on the human race, designed by men and apparently directed at female reproduction. The film has been dismissed by most people who have bothered to see it as a ripoff of The Terminator, but the similarities are few. It’s a thematic and tonal mess, careening between operatic pathos and slapstick comedy and then back, sometimes in the same scene, but there’s a lot going on here that makes it worth seeing.

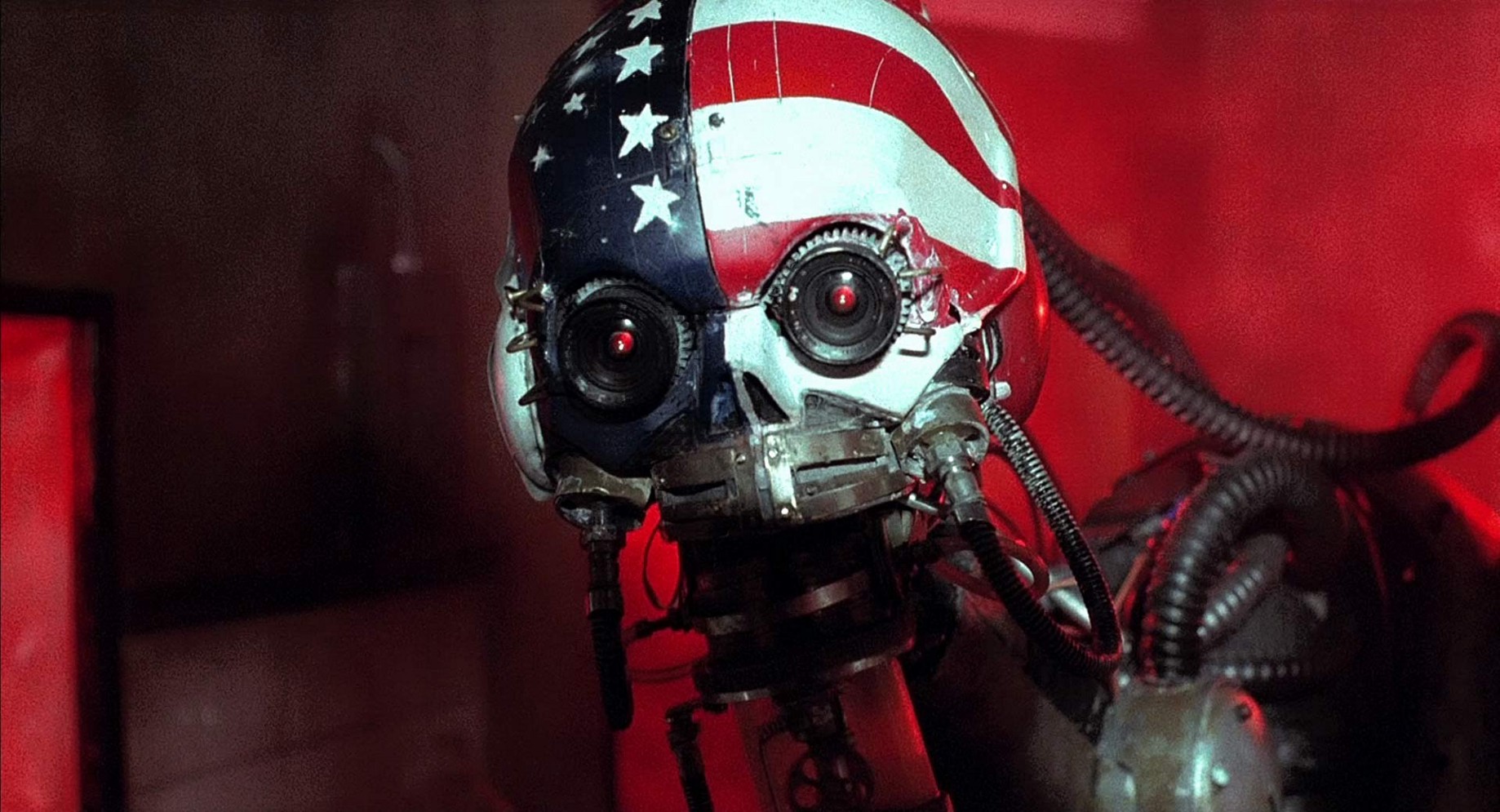

A “zone tripper” (Carl McCoy) scouring the desert for scrap metal recovers a robotic head and hand, which he takes to a scrap dealer to sell. But Moses (Dylan McDermott) buys the head off him first; he wants to give it to his girlfriend Jill (Stacey Travis). Jill, who lives sealed in her apartment and greets Moses with a geiger counter, is an artist who creates disturbing sculptures that uneasily blend the metallic with the organic, like something Georgia O’Keefe might have made had she known how to weld. She’s taken refuge against the irradiated world outside while molding its metallic relics into her art. She’s ecstatic about the head; she paints an American flag on it and uses it to top off a twisted mass of arachnoid metal (the identification of this robot with America doesn’t end there; we later learn that it can administer a poison that smells like apple pie). Although Jill stays in her apartment, she’s not safe even there; a rank and flabby neighbor named Lincoln Wineburg (William Hootkins) spies on her through her window and makes obscene phone calls. It turns out later that he even has the keycodes to get past her security system.

It turns out that the head belongs to an artificially intelligent robot assassin that can rebuild itself through force of will and is bent on the destruction of anything living. Moses learns of the head’s origins too late, and soon Jill is trapped in her apartment with the powerful, murderous Swiss army knife known as MARK 13 (and of course a guy named Moses knows to check the bible verse). At first the robot is kind of comical: the scene where it rebuilds itself is like a mechanized Ray Harryhausen effect, and even its first attack on Jill concludes with it covered in a sheet and thrashing around like E.T. But quickly it becomes apparent that the robot wants to not only kill her but violate her in the process. The first time we realize that it’s sentient is when it wakes up to watch Moses and Jill having sex. In a great transition, the robot’s voyeurism (and ours, too, since we’re watching the film) becomes that of Lincoln Wineburg, who is pleasuring himself while watching through an infrared video camera. Later, when the robot has rebuilt itself, it’s no accident that its attacks on Jill seem uncomfortably like attempted rapes. Its favorite weapon, aside from its buzz-saw (it has co-opted all of her tools in its self-rebuilding project), is a very phallic drill, with which it menaces her.

The robot turns out to be the logical extension of the government’s self-destructiveness. Nuclear war was just the start: the latest news is of the passage of a population control bill that will enforce sterilization for mothers with too many children; a newscaster quotes a politician that the plan provides “a clean break with procreation.” In a delicious offhand comment, we learn that the robot was built by Ferile Electronics, a name that calls to mind both “feral” and “fertile,” the former a good indicator of where humanity is heading and the latter a bitter irony. Disgusted with the government that could build such a creature—which, although designed as a combat unit, can’t distinguish between friend and foe—Jill says that it’s “the most useful thing they’ve ever given us,” because it will complete the job they started with a nuclear war: “That’s their population control.”

The film is most coherent when it’s dealing with the idea of government repression as sexual violence, which makes it kind of funny that it’s so unclear what’s going on with the male characters. I’m not sure what to do with Moses, for example: his odd name must signify something, but I’m not sure what it is, although the film contains several biblical references and the robot’s death scene looks like it’s praying. There’s a moment when Moses almost seems to make an extrasensory connection with Jill, which makes me wonder if there’s supposed to be something holy about him, but this is never developed. And then there’s Shades (John Lynch), Moses’s sidekick. There seems to be a hint, quickly dropped, that he and Jill have been seeing each other while Moses was in the Zone, but mostly his job consists of being present and ineffectual when Jill is in danger.

Don’t get me wrong: it’s not all Deep Thoughts, and there’s a lot here to please genre fans. The blood-red cinematography (by Steven Chivers) gives every scene the look of a fallout shelter, and Stanley is nothing if not a master of efficient filmmaking. Its brief 84 minutes flew by, punctuated by several scenes of garish horror that will satisfy any horror film fan. But the most notable thing about the film is what’s going on just under the surface.