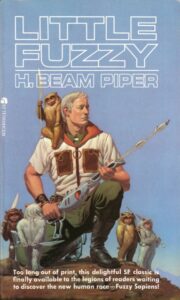

Little Fuzzy (H. Beam Piper, 1962)

Little Fuzzy (H. Beam Piper, 1962)

H. Beam Piper (American, 1904-1964) was 43 when he published his first short story, 57 when his first novel appeared, and 60 when he committed suicide. His 17 years as a professional writer saw him produce almost 30 short stories and seven novels, and another handful of stories and novels appeared after his death. In November 1964, distraught perhaps over what he thought was a stagnant writing career, perhaps over relationship issues, perhaps for reasons unknown, he shot himself with a gun from his extensive collection. Jerry Pournelle, the Ace Books editor who engineered the successful reprints of much of his work, says that Piper’s agent had died without informing him of several sales, giving him the mistaken impression that he was washed up as a writer. According to the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Piper’s Libertarianism prevented him from asking others for help in the months leading up to his death. And that’s a damn shame.

The Hugo-nominated Little Fuzzy (Avon, 1962; I read the 1976 Ace reprint with cover by Michael Whelan) is perhaps his most famous, definitely his most beloved work. It’s the story of Jack Holloway, a miner on the planet Zarathustra, which is controlled by the Zarathustra Company. One day, he meets and befriends a member of a small, bipedal, adorable, furry race he dubs Fuzzies. The creature is smart—it can make and use tools, it seems to speak a sort of language, and it makes and appreciates art. It adores Jack, and soon its whole family are doing adorable antics in his house. Word gets around about this new race, which causes big headaches for the Zarathustra Company: if the Fuzzies are sapient (i.e., if they have a human-like intelligence), then the Company’s charter for the planet is void and the Fuzzies have to be welcomed into the galactic federation of sapient species. The Company sends a team to discredit Holloway’s claims, a gunfight breaks out, and suddenly the Fuzzies are the hottest topic in the universe. The second half of the book is a combination of courtroom drama, as a judge must decide whether the Fuzzies are an intelligent race, and race against time mystery, as Little Fuzzy and his family are kidnapped by the evil Zarathustra Company and seemingly disappear.

It’s tempting to read the book as an anticolonial fable, which is at odds with what I’d have thought a Libertarian would think about the topic. It’s there on the surface: the Zarathustra Company is stripping the planet of its resources, and when the discovery of a potentially intelligent race puts that in jeopardy, the Company resorts to an intergalactic crime spree to maintain its control. Despite that, it’s not so black and white. Piper doesn’t object to certain aspects of colonialism, such as the extraction of natural resources—Jack’s prospecting for sunstones seems far more destructive than open-pit mining, for example, but he never has a come-to-Jesus moment about the wreckage he’s causing to the Fuzzies’ habitat. And essential to my hesitation is how darned cute the Fuzzies are. They’re furry and babyish and constantly doing adorable things, sort of like the mogwai from Gremlins (1984), minus the eating after dark thing. If they had been seven feet tall and given to eating humans for breakfast, I suspect that Pappy Jack wouldn’t have been such a crusader for their rights as members of the galactic federation.

Though it may or may not be politically progressive, it is a hell of a lot of fun. Piper’s writing is deft and propulsive, with no wasted space. He manages to create a world in a few pages, and I particularly liked the wild west in space setting. Piper drops in finely crafted if fleeting hints of how the world works—there’s a special attention paid to etiquette surrounding guns, which almost everyone carries, that reminded me of the increasingly elaborate myths of gunfights in the American West. My only real complaint is how obviously the deck is stacked in favor of the Fuzzies: almost as soon as the issue of intelligence is raised, any real threat of the Company winning evaporates, and the rest is merely the machinations of the legal system versus the increasingly hamfisted evil of the company.

The Fuzzy series had legs. Piper produced a sequel, Fuzzy Sapiens (first published with the terrible title The Other Human Race) in 1964, the year he died. Authors including Ardath Mayhar and John Scalzi have written books in the Fuzzyverse, and in 1984, a third Fuzzy book by Piper himself was discovered and published.